I bitch about my Wi-Fi modem stalling. I should be ashamed of myself.

My great-grandmother rode in horse-drawn carriages until she was in her mid-20s, and my grandmother gave birth to my mother five years before Apollo 11 landed on the moon.

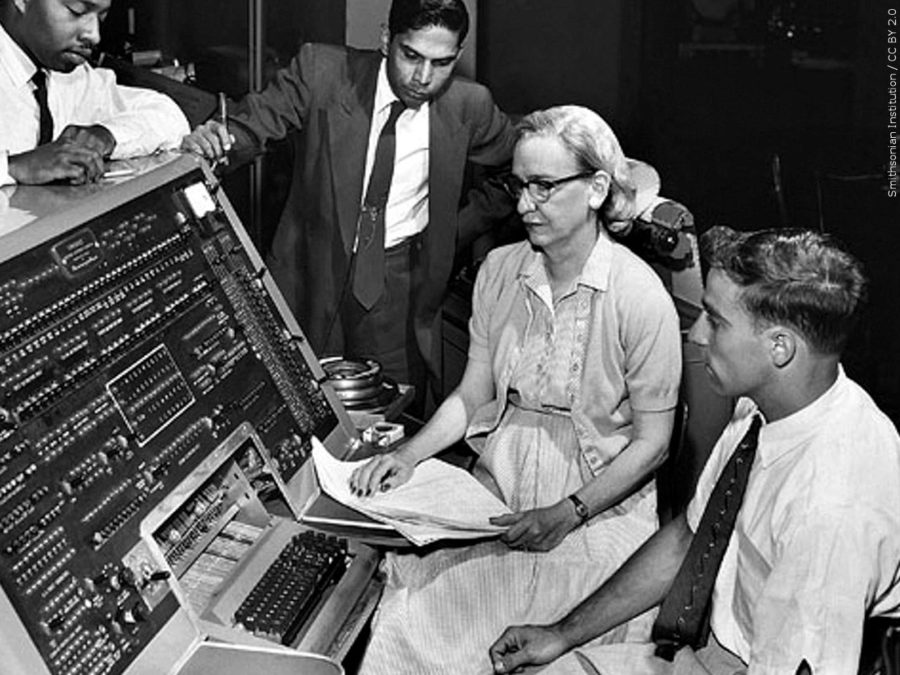

I was part of the last generation to live in houses with phones attached to the walls, and my first computer looked like mission control from a Cold War espionage movie.

Now, I Facetime from my smartphone like I’m on the bridge of the Enterprise, I charge my books and my cigarettes from a USB port and I carry around the modern equivalent of the Library of Alexandria in my pocket.

For a long time, I was jealous of all that my great-grandparents witnessed, going from horse and buggy to space flight, but I’ve actually seen twice as much technological advancement in a quarter of the time, just in a different way.

It’s a long story.

Almost 2 million years ago, a variety of early hominin began making tools commonly referred to as “choppers” today, one of which is still on display at the British Museum, the oldest manmade object in its collection.

Whatever you’re envisioning when you think of a prehistoric tool, make it simpler and you might be close. They were fist-sized cobbles fractured to create a sharp edge — and these tools were mass-manufactured by Australopithecus garhi in present-day Tanzania for over a million years before any real change ever occurred.

It took 100,000 years – over 15,000 modern lifetimes – and the evolution of a new genus of hominin before this design was improved upon by Homo erectus’ Acheulean “hand axe” — and even then, it’s a relatively small change. The Oldowan chopper was to the Acheulean hand axe what the iPhone 5 was to the iPhone 6: a little thinner, a little more efficient.

It takes another million years and the emergence of two new hominin species before we start forging metal, but that’s where things get interesting.

In the span of 5,000 years, Egypt saw both the creation of its Old Kingdom monuments and Napoleon’s armies marching along the Nile plundering those monuments to be stocked in the Louvre as antiquities.

What this means is that in less than a quarter of the time it took our species to work out how to make a sharp rock slightly sharper, we experienced every technological and cultural innovation between the reign of King Tutankhamen and that of Queen Victoria – everything from the first papyri of the Torah to Darwin’s “On the Origin of Species.”

Only 156 years after that, we arrive at our globalized, digitized world – drones, fiber optics, the International Space Station and 40 different flavors of Ben & Jerry’s.

Moore’s Law — the doubling of the number of transistors on an integrated circuit each year since its invention, allowing for rapid progress in data processing — appears to be part of a much longer trend. All technology, not only digital, advances exponentially.

But what does that technology say about us? Archaeologists today sometimes refer to cultures that existed in antiquity by what they made prolifically.

The Bell-Beaker culture of Western Europe, for example, was given that moniker because of the inverted-bell-shaped vessels found at sites once occupied by these prehistoric peoples. Analysis suggests they were used for drinking mead, smelting copper and containing funerary ash. These vessels were important to them.

I imagine archaeologists millennia into the future will refer to my generation as the Black-Mirror-Box culture. If some biblical-scale cataclysm were to swiftly end the digital era, these boxes would be found on nearly 7 billion desiccated bodies. These boxes were important to us.

But what would those artifacts say about us as a culture if they were to be analyzed 15 generations down the line (or if Ray Kurzweil and Aubrey de Grey are correct, only five or so generations)?

As we interpret the ideals of civilizations lost to us in time through the material remains they left behind — technology, especially —we, too, are writing our legacy with what we create.

The question is what we want that legacy to be.