The 20th century’s eminent expert on folklore and myth, Joseph Campbell, writes in his book “The Power of Myth” that an increasingly globalized world will need a common myth in order to survive.

This is because literalized myths — religions—began degenerating more rapidly in the early 20th century as the world became more globalized. Yet over the last few centuries, while thousands of religious orders across the world have vied for influence in the lives of more cosmopolitan individuals, a new myth was being written in the background, quietly, one still being written today.

All over the world, scientists have been using a methodical technique to gather evidence of very specific truths, which when added to the greater mosaic of the collective sciences paints a poignant, dynamic representation of our universe, what we are and where we came from — even what the universe’s ultimate end will be.

It’s the skeptic’s myth. It doesn’t require blind faith but rather demands proof. Depending on the evidence, a statement can be said to be more or less true, but this myth offers no singular, ultimate truth. Still, this doesn’t make it any less awe-inspiring. It goes like this.

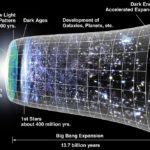

Nearly 14 billion years ago, existence erupted out of a point no larger than the particles of an atom. Instantaneously, it blasted through a perfect void, generating nearly 14 billion light-years of matter and space. And it’s still expanding.

When this universe was in its infancy, only 200 million years old, the first stars lit up the pitch darkness like grand, cosmic chandeliers. Just over 4 1/2 billion years ago, our planet formed. Within 1 1/2 billion years, what would become the continents began rising out of the ocean — and the first, single-celled life appeared only half an eon later.

Over the next 3 billion years, that life carried on, subtly changing with every generation, each a part of an infinitely intricate and diverse tree of life. Seven million years ago, in the primordial forests of the African continent, one remarkable branch of that tree became distinct from the rest of the animal kingdom: the earliest hominin.

It was brilliant. It was creative. Within 4 1/2 million years, it had begun changing the world around it, striking stone tools and learning language — creating culture.

Only 2 1/2 million years after the first stone hand axes were chipped at Olduvai Gorge, modern humans raised the walls of their first civilization, and just 8,000 years later, I keyed these words on a machine that streams information through the air.

Granted, this is an extremely abridged version of this story, told only through the scopes of astrophysics, archaeology, geology and paleontology, among the countless scientific disciplines. But this new myth has a certain drama and grandeur to it, and I’m hard pressed not to have an experience that’s (for lack of a better word) religious when looking at this model.

But not everyone shares this sentiment. Many actually take offense to the idea of being descended from and alongside apes — yet it never seems to get brought up that, if their ancestries were to be traced back far enough, they’re descended from algae as well.

According to this myth, every living thing is related at some level or another. This has been a tenet of dozens of Eastern schools of thought for over 2,000 years — in fact, there’s nothing about this new myth’s scale or poignancy that doesn’t rival that of the classical world religions — not to mention that the method used to write it also wiped out polio and propelled us into the cosmos.

At the end of the 15th century, European explorers set sail looking for the geological vestiges of creation: the rivers of Paradise and the chasm torn through the Earth when Lucifer was cast down from heaven. They didn’t find it.

And believers have persisted in their search for centuries. Six years ago, a gaggle of Christian pseudo-archaeologists sought out the remains of Noah’s ark and claimed with 99.9 percent certainty that they’d found it atop Mount Ararat in present-day Turkey. They didn’t.

This new myth is the first of its kind. Where the world’s great religions have always sought evidence to validate their claims, this story is told by the mountains of empirical evidence themselves, collected by scientists from nearly every nation on Earth working together for nearly 200 years.

Perhaps this is why 67 percent of scientists don’t subscribe to any religious belief system while 83 percent of the general public does. They’ve been introduced to the new contender of origin stories, an epic that confidently stands on the shelf right alongside Genesis and the Rigveda.