While watching a TED talk about whether or not we are killing creativity in young people by shoving STEM down their throats, I crystallized an attitude I have been incubating for some time. It’s this: we need to decouple success from financial gain.

The example in this particular TED talk was a girl who did not do well in her classes in public school. It was found that she learned better when she was able to dance. The valid point was that not everyone learns the same way. Is there a way to accommodate kids who learn by adding motion, music or hyper-competitive arm wrestling? If the answer is yes, then how can we work it into a curriculum?

Money. The answer is money. It’s a stupid question, really.

But in this example, the kicker was that this girl got a chance to attend a dancing school and went on to run Julliard. She became successful—which is awesome, obviously.

However, in all seriousness, how many people can head up Julliard? How does this number, which I am assuming is witheringly small, compare to the many people would love to dance for a living, which I am guessing would be vast?

This is a real issue in America, specifically. We value power and money. Success is almost synonymous with cash and fame, but cash and fame in the arts are rare—exceedingly rare. For every famous artist you know, there are countless struggling people who will get nothing from their efforts—not money, not fame, not even a pat on the back from their buddies who find their “hobbies” sort of charming, but mostly a waste of time.

I play the bass. I used to play it for local bands. Three of those bands made records that you could buy. You didn’t. I would be floored if anyone reading this ever heard one of the songs from one of those records. I played in bands for a long time and, near as I can figure, when all was said and done, I lost around $3,000 for my efforts. I am not famous. I am not rich.

But I argue that I am successful.

I have met some of the coolest—and a few of the worst—people you could meet. I have played in front of all kinds of crowds. I learned how to deal with very powerful personalities to get something done. I got to create and then watch people react to my creation. I got to hear a song that I helped create on the radio. I can sit in with anyone, playing any style, even above my talent level, because I learned to be a part of a functioning group. I lost my fear of being on stage and so learned to control my own ego. I got to travel a bit, I got to flirt a little, I got to drink a tad and I have some of the best memories you can imagine.

And these moments have influenced everything else about my life in ways too numerable to list. They added value to who I am and what I can do. That is success.

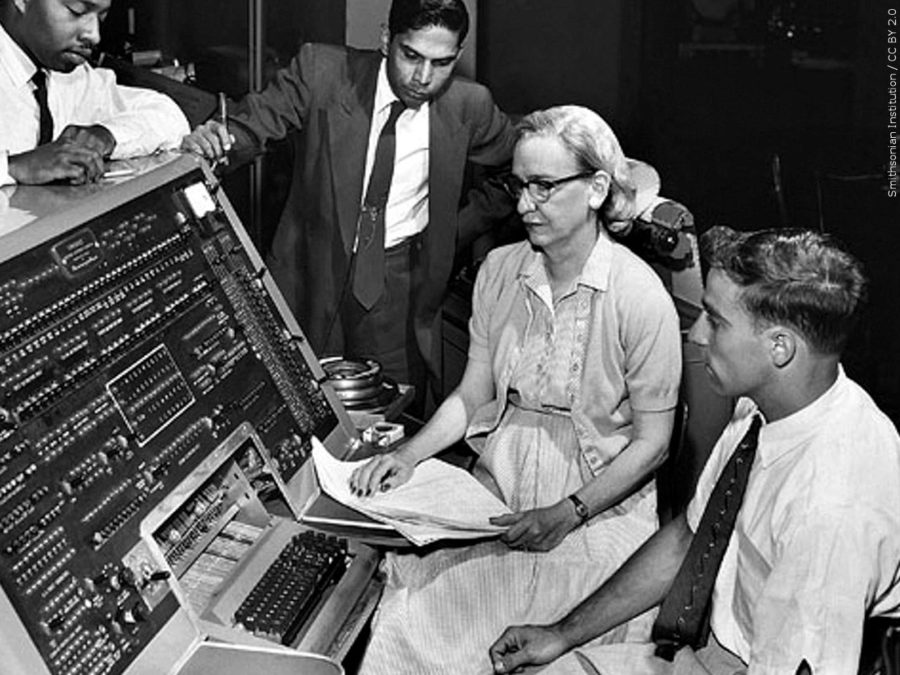

We need dancers, without question, but we need more researchers, more mathematicians, more scholars and more engineers. If all the dancers feel like they have failed if they don’t run Julliard, how much passion will they place in their STEM careers? Going through the motions doesn’t help us much.

Why can’t the dancer who designs the next-gen medical device consider herself a successful dancer? Why can’t she take all that fluidity, power and finesse and let it overflow into her rigorous research and development? And if she becomes stumped, why can’t she walk out of the lab, turn up the volume and throw-down relentlessly until inspiration takes her, body and mind?

After all, she is creating, and the mental muscles that direct her motions can inspire the ones that lead to discovery and innovation.

We push STEM because we need STEM. But why is it either/or? Why is the only successful dance the one that gets you to Julliard?