From 2011 to 2017, California experienced severe drought. The drought ravaged the state’s agricultural industry, and residents watched their lawns die or opted to replace them with artificial turf.

As urban growth and the effects of climate change place a greater strain on traditional water sources around the world, some academics and entrepreneurs are seeking ways to cheaply provide fresh water from far away sources to drought-stricken or otherwise dry areas.

Mihail “Mike” Cocos, associate professor of mathematics, is doing what he can to revolutionize water delivery systems. He was able to share his experience at a lecture in Tracy Hall on Jan. 15.

While completing high school in his native country, Romania, Cocos struggled with mathematics, but he found physics to be fascinating.

“My math teachers told me that I absolutely needed to have math skills to be successful in physics,” Cocos said. “So, I took as many math courses as I could.”

He eventually made mathematics his career. He now teaches a range of quantitative sciences, from college algebra to calculus and even theoretical mathematics.

Cocos’ mathematical expertise caught the attention of Romanian businessman and engineer, S. Dorian Chelaru. Chelaru conceived the idea of transporting fresh water from Sitka, Alaska to Los Angeles. However, Chelaru wanted to design a transportation method cheaper and less environmentally impactful than a pipeline.

Chelaru decided to study the possibility of transporting the freshwater by sea. Using his engineering background, he hypothesized that the best way to transport extremely large quantities of water would be to do so on supersized, tanker-like, 2,000 foot-long submarines.

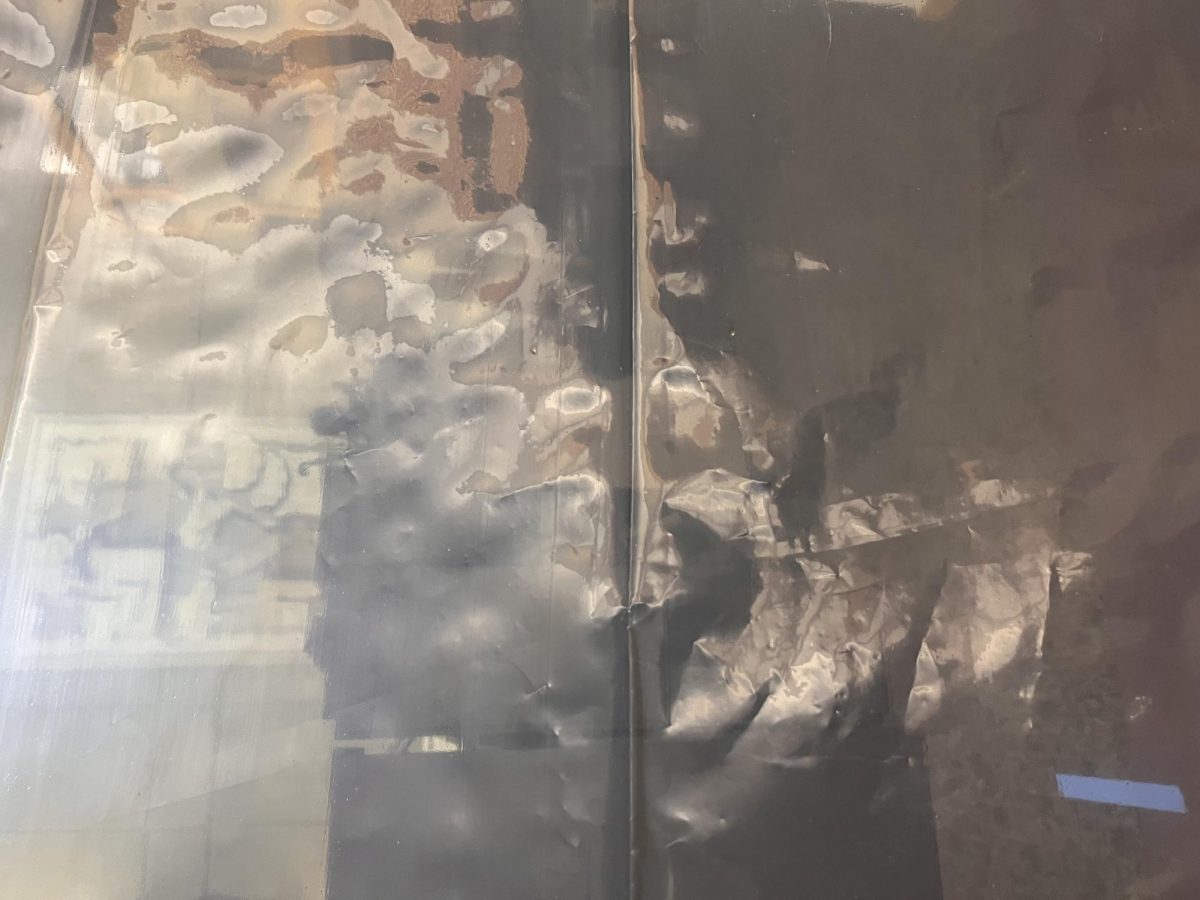

Chelaru proposed manufacturing the ships out of concrete to resist corrosion. The submarines would contain bags, or membranes, that would hold the freshwater. According to Chelaru, submersibles have the advantage over surface vessels because a submarine can avoid the destructive power of the ocean’s waves and are less prone to collision.

However, he needed further guidance regarding the massive proposed size of the ships, the water pressure on the hull of the ships and the sheer weight of their freshwater cargo.

So, Chelaru decided to collaborate with Cocos.

Chelaru and Cocos used calculus to determine the necessary designs that would avoid buckling and structural failure. Cocos further used mathematics to confirm the best shape of the membrane needed to safely transport the water.

According to Chelaru, his water transportation system would be relatively simple compared to a pipeline. The origin, Sitka, Alaska, would simply need a pumping station to which the submarine would dock and receive the water. The submarine would then travel autonomously to its destination in Los Angeles, where another pumping station would remove the water and make it available to the local water supply.

Chelaru claims the total estimated cost, including the pumping stations and necessary submarine vessels, would be around $410 million, and the cost to water customers per gallon of water would be cheaper than current rates.

However, both Cocos and Chelaru realize that while the mathematics may make sense, the idea has plenty of opposition.

“It really is an ambitious plan,” Chelaru said. “But it is not a new idea.”

He lamented California’s historic lethargy in planning, approving and constructing irrigation projects.

Some of Cocos’ Weber State colleagues, who attended the lecture, also voiced their mathematical concerns over the structural limits of the proposed submarine.

“Your problem is going to be the waves,” John Sohl, professor of physics, said. “There are many different types of waves in the ocean, and there is also the shearing force of ocean currents.”

Sohl believed that Cocos and Chelaru had not taken these forces into account.

Another audience member voiced his concern about the wasted cost of the return trip to Sitka. The submarine would be empty; therefore, it would not generate any revenue.

Chelaru admitted that one advantage of a pipeline was the ability to produce continuous flow and revenue, but he remains optimistic about the system’s overall savings in transport costs and maintenance.