From his famous last words, “You’re fired,” on the reality television show “The Apprentice” to becoming President of the United States, Donald J. Trump has defied the rules and expectations of standard political practices, resulting in an outpouring of animosity regarding how the U.S. governs its elections.

In a historically-jarring election, Trump accumulated at least 270 electoral votes needed to become the president-elect. His opponent, Senator Hillary Clinton, lost the election because of the Electoral College’s voting system, despite having won the popular vote among voters.

The results sparked outrage among voters because many believed their votes were, ultimately, useless. Voters demanded Washington throw away the Electoral College entirely and resort to a populous voting system for future presidential elections.

With the national spread of equal rights activists and social movements taking action in recent years—like the LGBTQ community, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo—it seems possible that Washington could do away with the Electoral College, forming the idea that we all have equal rights within our votes in our presidential elections.

Thus, the Electoral College found its place in the mud of a corrupted political voting system—with Trump promising to “drain the swamp” of corrupted lobbyists and politicians from office.

But shortly after Trump’s inauguration, it seems that corruption rapidly crawled into his administration through ongoing rhetoric, numerous investigations and—in recent news—his attempt to have the president of Ukraine investigate former Vice President Joe Biden and his son, Hunter Biden, prior to the upcoming 2020 election.

Will political systems like the Electoral College ever be reformed? If so, how do we elect politicians who will serve justice for a voting system with less corruption and a prosperous future?

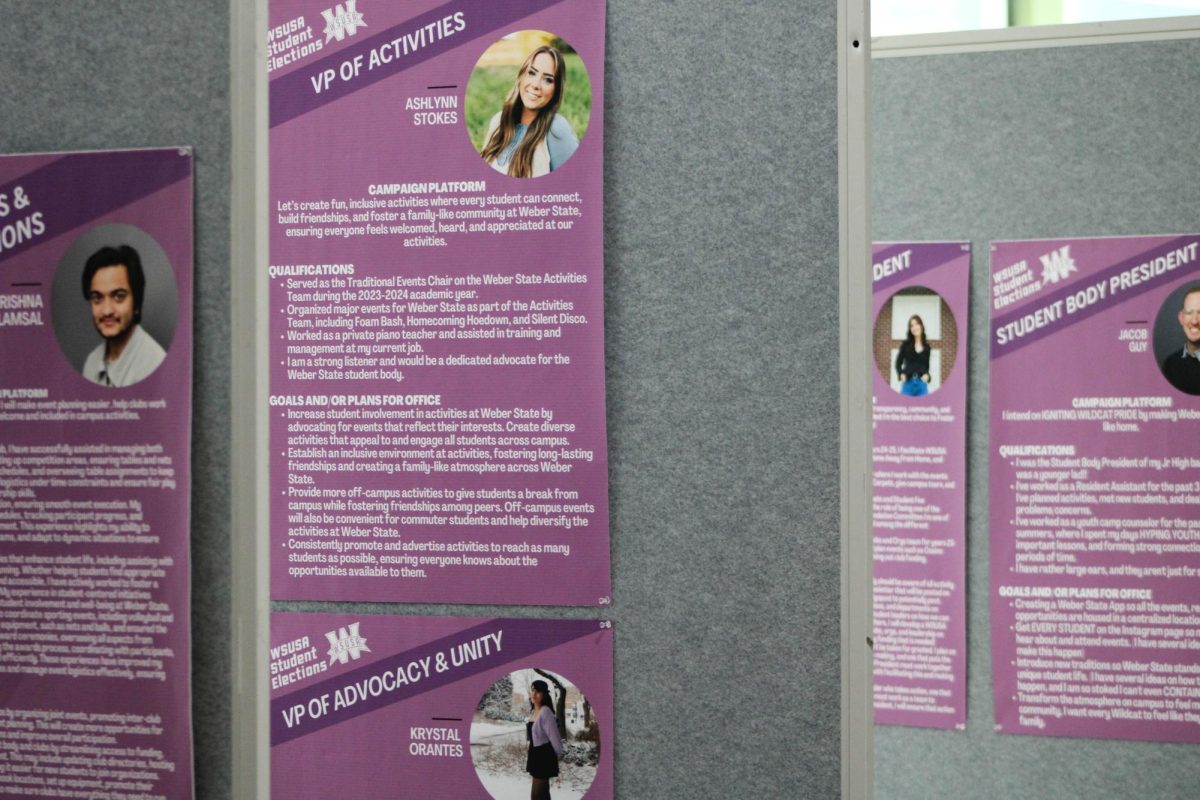

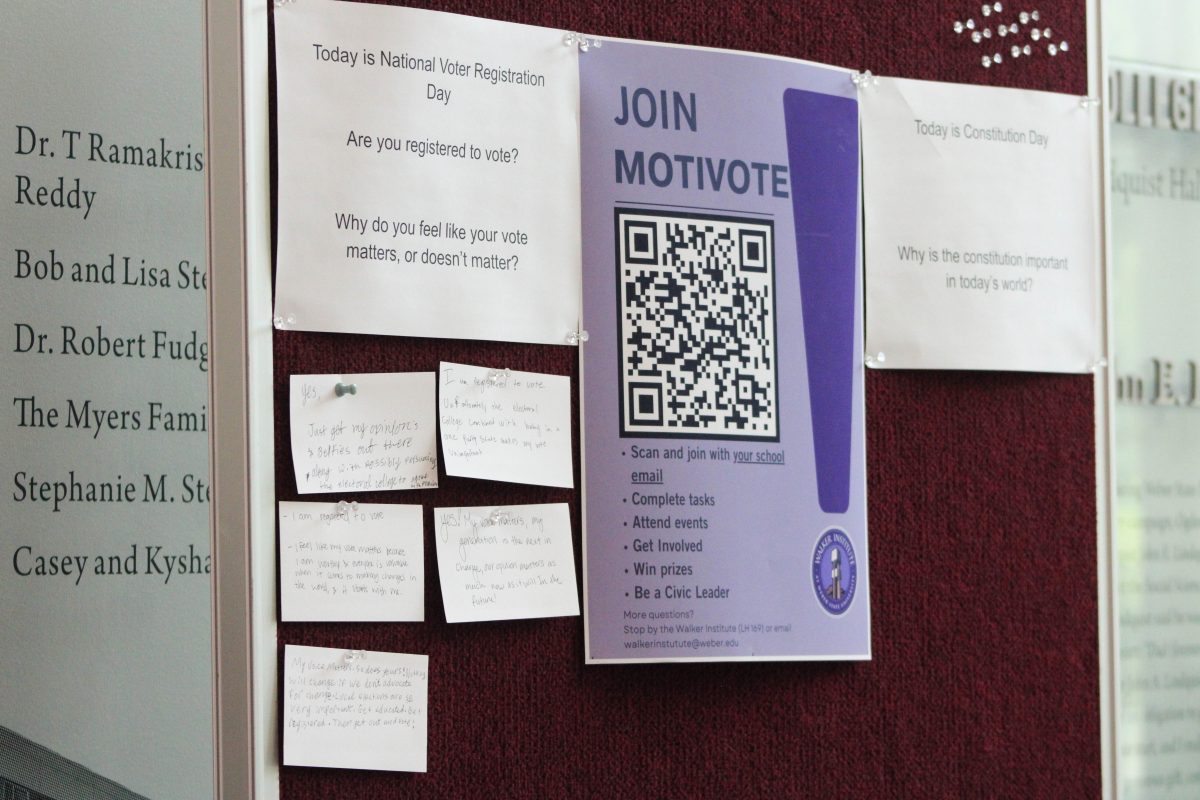

In the midst of Weber State University’s constitution week, political science professors Dr. Thomas Kuehls and Dr. Leah Murray organized a debate in Barlow Lecture Hall. Kuehls and Murray shared their opposing views on the subject matter to an audience of about 60 people.

Kuehls, in favor of removing the Electoral College, arrived to the debate dressed as James Wilson, one of the U.S. founding fathers and a signatory of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Kuehls addressed himself as Wilson throughout the entire debate.

“My name is James Wilson,” Kuehls said. “I was delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and the first person to come up with the constitutional convention we know now as the Electoral College.”

Influenced by Kuehls’ eloquence, some attendees engaged in the discussions through mockery fashion, beginning remarks with, “My question is for Mr. Wilson.”

Various attendees knew about the Electoral College but were unsure what the Electoral College’s purpose is and how it functions.

The Electoral College was established so that the government and the states wouldn’t have total control of who gets elected in and out of office.

In theory, the Electoral College seems like a gift to the people by the government.

But an underlying component in the voting system is that politicians tend to focus their campaigns on a group of perennial “swing states,” an argument that Kuehls made.

These states typically have a recurring theme where they could reasonably be won by either a democratic or republican candidate. Thus, a candidate will campaign in these states to attract voters.

In the last few elections, the swing states have included Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Virginia and Wisconsin.

Kuehls argues that a popular vote election isn’t going to narrow the system and instead “require candidates to campaign across the country,” focusing their campaigns in all states, not just the swing states; this would allow for every vote in every state to be equally accounted for.

In hindsight, Murray wants to keep the Electoral College and “remove the perversions and operate the way it was intended.”

Murray said she would get rid of national campaigns, comparing them to Superbowl advertisements and the end result of the “demigods we’ve seen elected in office.”

“It’s led to painful polarization with people reporting that they’re exhausted. They’re thinking about politics, and they’re just tired that there’s fatigue around this,” Murray said. “They don’t want their children to grow up and marry someone from the other party. It’s insane with that level of animosity, and I tie it directly to allowing people to vote for the president and having the states require electors to track that popular impulse.”

WSU student, Cole Larson, favors the Electoral College and thinks that some of the more unsavory traditions that the U.S. was founded with in 1776, such as slavery and a lack of equal rights—including voting, would otherwise persist to this day.

“Democrats are calling to abolish the Electoral College,” Larson said. “We need to keep the Electoral College because if we had a popular vote election, there might still be segregation and slavery today.”

It’s nearly impossible to create a scenario with “what could have been” if the Electoral College hadn’t been established, but it’s seen as our civic duty to vote in our elections, whether it’s on a national or local level.

To take away those rights is unprecedented, considering our nation’s history that led to its current form.

But is the reason why our nation is divided because of the Electoral College, a lack of public political knowledge or the scope of attention that our elections bring through public interactions, televised campaign rallies and social technologies?