Galveston, Texas. June 19, 1865. Federal troops took control of the state to command that all enslaved people be freed.

U.S. Gen. Gordon Granger stood on Texas soil and read General Order No. 3: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863. Two and a half years later, slaves in some non-Confederate states were still not free. Many slavers had moved to Texas, which was viewed as a safe haven for slavery.

Granger’s proclamation officially freed the last slaves in the United States in America, some 250,000 people. Celebrations broke out across the country, and Juneteenth, the holiday commemorating the official abolition of slavery, was born.

In 1979, Texas became the first state to make Juneteenth an official holiday. Today, it is recognized as a state holiday in 47 states, but efforts to make it a national holiday have stalled in Congress.

I didn’t learn any of this in school. In fact, I had never heard of Juneteenth until after I graduated high school. In Black-majority areas across America, Juneteenth is celebrated with music, barbecues, prayer services and more. In Utah, Juneteenth is hardly celebrated at all.

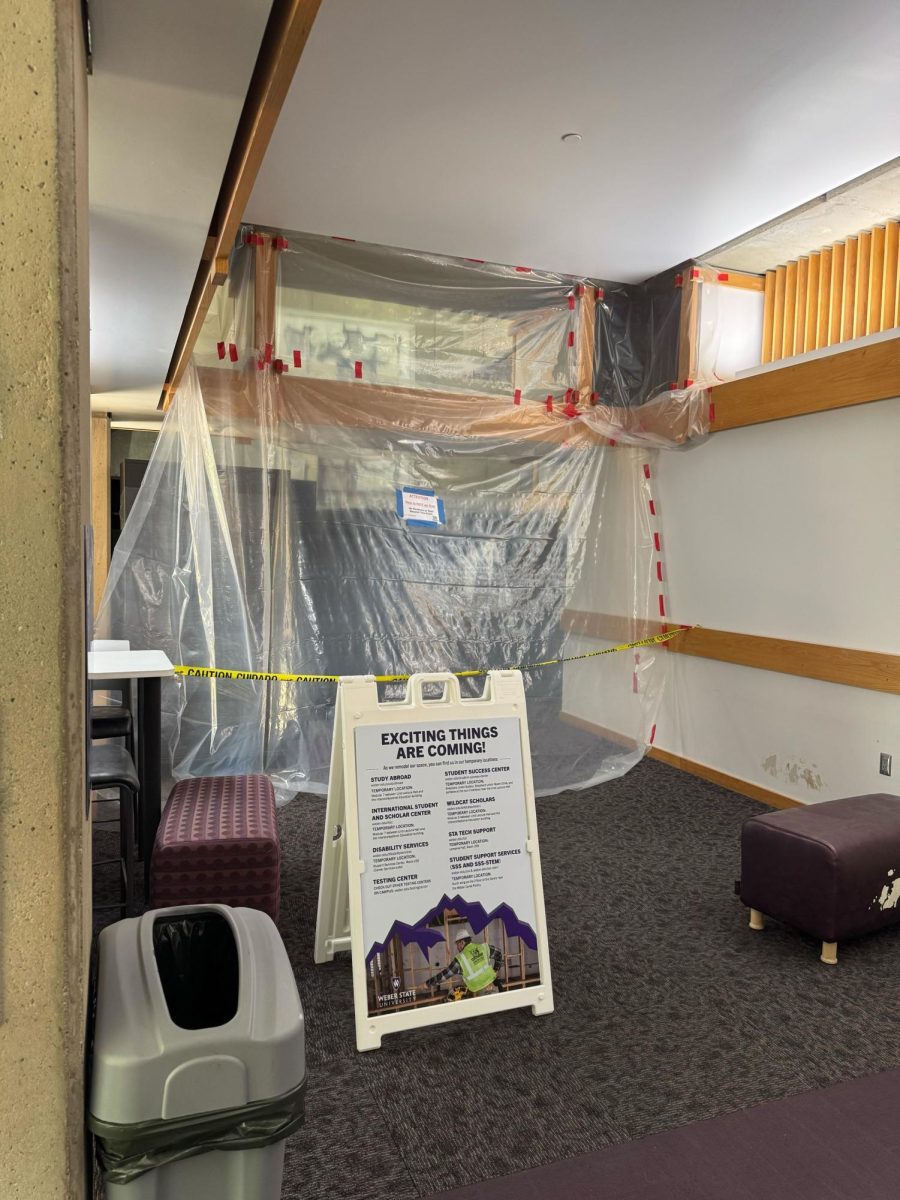

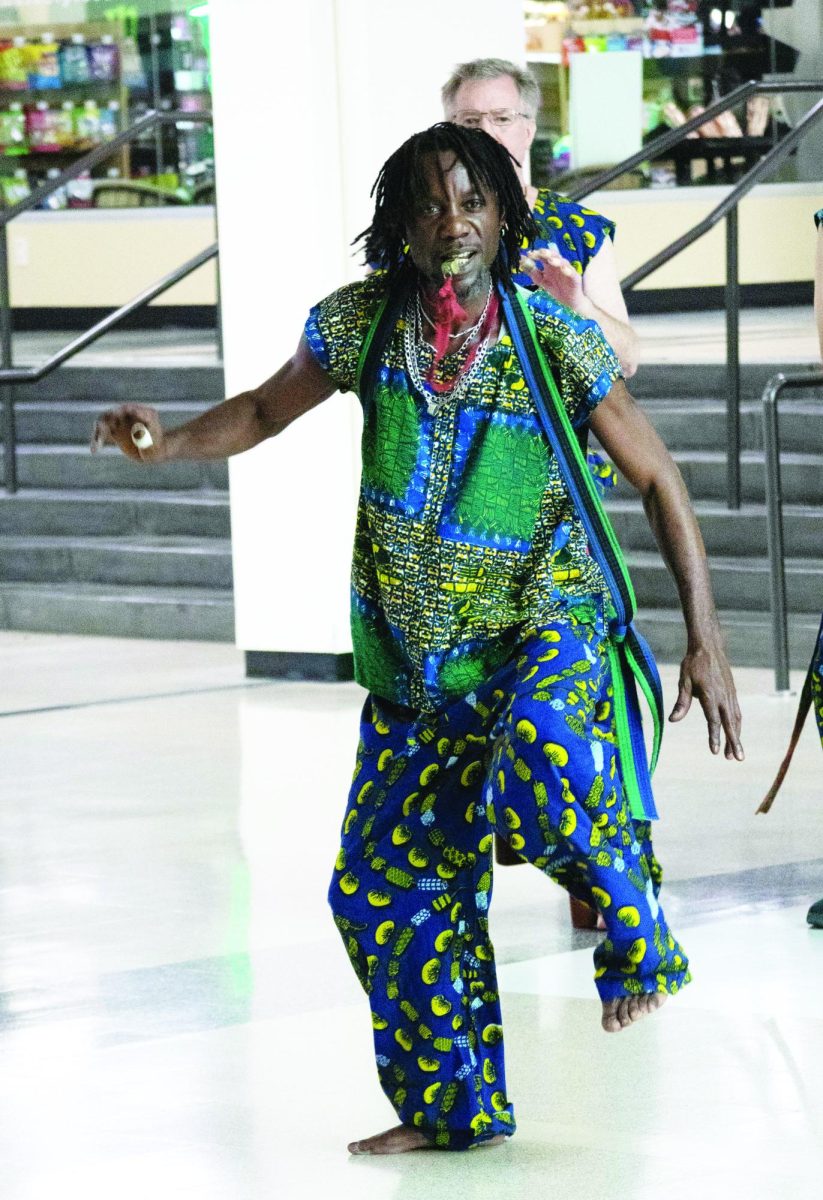

Weber State University does celebrate Juneteenth with the annual Freedom and Heritage Festival. This year, many of the events were held virtually, but students were still able to watch films and listen to town halls featuring Black leaders and activists.

ABC4’s coverage of the event began with the sentence, “There’s a possibility you’ve heard of Juneteenth.”

However, many students haven’t. Juneteenth isn’t in the required curriculum for Utah schools, even universities. I received my Bachelor’s degree without a mention of the holiday — and I’m a History minor.

Maybe Juneteenth doesn’t seem like a critical holiday in Utah, considering our population is 90 percent white, but racism has existed here since our state was settled.

The first group of pioneers to reach the Salt Lake Valley included enslaved members. Slaves were bought and sold here. When slavery was outlawed, Utah joined other states in passing “black codes”: laws that targeted Black workers and set the stage for Jim Crow.

In 1925, a Black coal miner named Robert Marshall was accused of murdering a county marshal. Despite there being no witnesses to the crime, Marshall was apprehended and taken to jail.

A mob commandeered the vehicle, dragged Marshall to a farm in the area and lynched him.

A group of 100 Black workers in the county pooled together money to pay for his funeral expenses. They didn’t have enough to afford a headstone.

Utah has a history with racism running as deep as any state. Black people have been killed here. They’ve been denied places to live, eat and perform.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which has had a religious stronghold since pioneers settled here, didn’t allow Black members to hold the priesthood until 1978, more than a hundred years after slavery was abolished.

White people are still learning about Juneteenth, while millions of Black people celebrate it every year.

Juneteenth was a bigger story than usual this year, thanks to President Trump scheduling a rally over the holiday in Tulsa, the site of one of the worst race massacres in the history of America.

I didn’t learn about the 1921 Tulsa massacre in school, either.

Later, Trump took credit for educating Americans about the holiday.

“I did something good,” Trump said. “I made Juneteenth very famous.”

White people shouldn’t be learning about significant holidays because the president tried to overshadow it with an extraordinarily-irresponsible gathering in the middle of a global pandemic.

We don’t have an excuse anymore. We should be learning about Juneteenth. We should be teaching our children. It should be part of the required curriculum for every school, in every state.

We celebrate the slaughter of indigenous people on Columbus Day. This year, we’ll celebrate America’s independence from Britain twice. Yet, Juneteenth is still not a national holiday.

Until we are committed to making Black history as significant as white history, we will continue to live in two Americas. One for the oppressors. And one for the oppressed.