On Nov. 6, 2018, I lined up outside my city council building to vote. Though the race for Senate and my local representatives seemed airtight, Utah had several propositions up in the air.

Prop 2 aimed to legalize medical marijuana, Prop 3 would expand Medicaid to cover low-income adults and protect children and Prop 4 would create an independent redistricting commission with the aim of mitigating gerrymandering.

After voting for all three measures to pass, I went home to watch election coverage, and I watched votes come in a state of near-disbelief. Even after The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints publicly opposed Prop 2, it passed. Prop 3 passed with the biggest majority of the three, while Prop 4 passed with razor-thin margins.

When Democrat Ben McAdams managed to defeat Republican Mia Love in Utah’s fourth district, it seemed Christmas had come early. Utah voters had shown up and voted with empathy and understanding.

A month later, Utah’s legislative session began, and most of the November victories were wiped away quietly and succinctly.

The Utah Medical Cannabis Act replaced Prop 2. The replacement legislation overhauled the medical cannabis distribution system. The LDS Church advocated for the bill change and worked with the Utah Patient Coalition to find an initiative they could both agree on.

While medical marijuana is now legal, the new bill has strangled Utah’s medical marijuana program in red tape and blocked many patients from being able to receive cannabis treatment.

After the new bill passed, medical cannabis advocates announced they would be suing the state. The heads of Epilepsy Association of Utah and Together for Responsible Use and Cannabis Education accused legislators of ignoring voters to appease the LDS Church.

The lawsuit argues that the church’s involvement in the legislation violates the constitution, which reads: “There shall be no union of Church and State, nor shall any church dominate the State or interfere with its functions.”

The Utah State Supreme Court took the case and will hear arguments against the state, scheduled for March 25 in Salt Lake City.

After Prop 2 took a beating, legislators tackled Prop 3. SB 96 replaced the proposition and was signed into law by Gov. Gary Herbert. Legislators claimed the sales tax hike proposed by Prop 3 would not have been enough to cover everyone, and the expanding costs would have hurt the state budget.

Ultimately, the new bill cut healthcare for tens of thousands of Utahns and helped social interests and politicians. If The Utah State Supreme Court decides in favor of Prop 2, the decision could also affect Prop 3.

Prop 4 is alive, but not for long. Because redistricting won’t begin until 2021, legislators left it out of this year’s session. Several Utah lawmakers have raised concerns with Prop 4, claiming their conflicts have nothing to do with personal objection.

But when you’re a representative elected in a conservative area that was carved out of Salt Lake City — for example, say, Rep. Curtis Bramble, who opposes Prop. 4 — your personal interest would be to keep Prop 4 far away from the law. Gerrymandering is the process of manipulating the boundaries of an electoral constituency to favor one party or class, and several Utah legislators likely have their seat solely because of gerrymandering.

Lawmakers slice liberal sections of certain cities to keep the majority conservative. Salt Lake City is cut into four parts, with conservative areas like Provo absorbing more liberal neighborhoods.

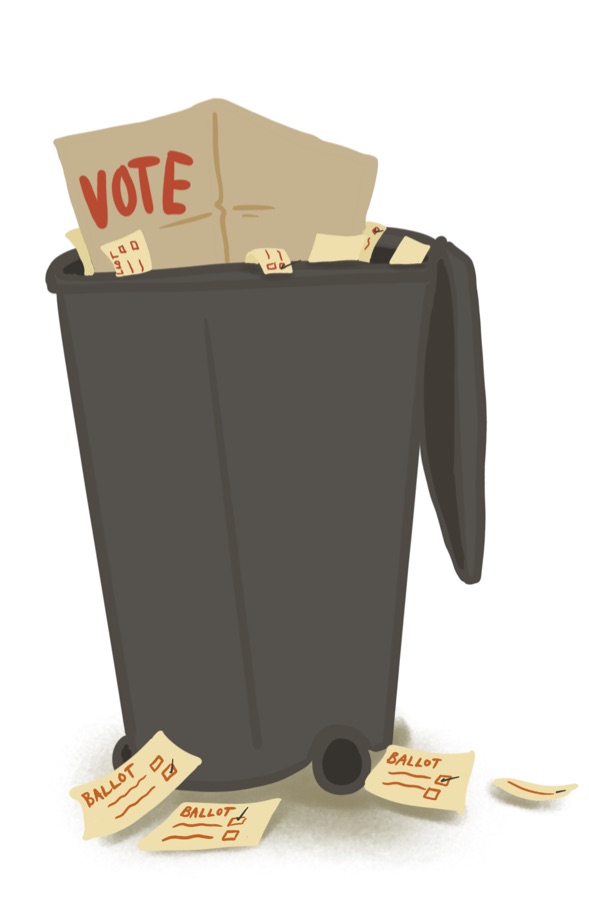

Gerrymandering is a process that only favors lawmakers. Voters are being manipulated into sections to silence their vote.

There’s no need to wonder why America lower voter turnout than almost any other developed nation. Why did I wait in line last November if my voice was going to be ignored anyway? Utah voted for medical marijuana, Medicaid expansion and an independent redistricting commission.

Lawmakers took it into their own hands to wipe out the first two propositions, and the third won’t last another legislative session.

I was told that if they won’t listen to my voice, they’ll listen to my vote. It’s now clear that my local lawmakers won’t listen to either. Luckily, I have one power that they can’t rewrite: the power to vote them out of office.