In 2009, Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble, professor at the University of Southern California, questioned Google’s search algorithms about specific phrases. When she searched phrases like black, Latina or Asian girls on the images tab, the photos predominantly consisted of pornographic images.

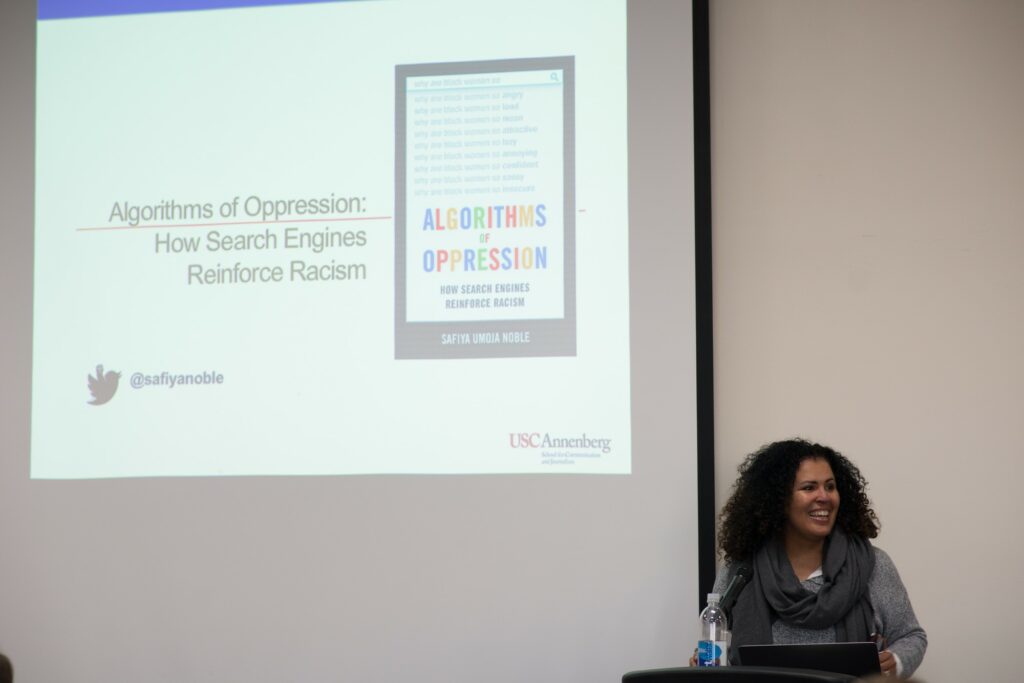

Noble, a researcher on gender and race bias in media, discussed search engine algorithms for LingoFest 2019 on Feb. 1 at the Elizabeth Dee Shaw Stewart Stadium. She was sponsored by LingoFest and the 4th Utah Symposium on the Digital Humanities.

LingoFest is an annual two-day conference that invites technologists, students and academics to speak on a variety of topics. According to WSU’s webpage, Digital Humanities explores the connections between humans and machines, following a precedent of technological advancements in Utah, such as the transcontinental telegraph.

In her book, “Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism,” Noble stated her goal was “to get people thinking and talking about the prominent role technology plays in shaping our lives and our future.”

The United Nations launched a campaign in 2013 to discover what genuine Google searches were. Comparing various parts of the world, they used Google’s autocomplete to see suggestions of beginning statements.

When experimenters typed “women should” into Google, they found that “stay at home” and “be in the kitchen” were among the top finishing statements. As for “women cannot,” the top suggestions were drive, have rights and be trusted.

Kabir Ali, a student from Baltimore, recorded himself Googling “three black teenagers” and “three white teenagers.” “Three black teenagers” gave Ali image results of mugshots and gang affiliations. When Ali searched “three white teenagers,” the images primarily showed teens studying.

With one word change, the results were vastly different. Ali tweeted the video, and it went viral.

When Google heard about this, they responded by saying that they do not have control over the algorithms. However, Google admitted they have control over what users can find in their images.

Shortly after, Google inserted one photo into the search of “three white teenagers,” of a white teenage criminal who was sentenced to fifty years in prison after he committed a hate crime against an African-American man.

Noble conducted research on Google algorithms by typing in “black girls.” She searched this assuming her daughter would one day search the same thing. When Noble left it at the two words, she said the first page contained almost exclusively pornography.

Because of those results, Noble had concerns for her daughter. She did not want her daughter see those images and to think that all African-American women were perceived as sexual objects.

Robert Fudge, professor of Philosophy at WSU, urged students and teachers to be aware of Google’s algorithms, as they might lead people astray from the truth.

“The information we find on Google’s first page is determined by these algorithms, and it isn’t necessarily the best information that’s available,” Fudge said.

After hearing of more backlash from the content of their search suggestions, Google addressed the issues.

“An important part of our values as a company is that we don’t edit the search results,” a worker for Google said. “What our algorithms produce are the search results. People want to know we have unbiased search results.”

Ami Comeford, professor of English at Dixie State, said that she never thought about the idea of Google being a biased search engine. However, Noble changed her thoughts on it.

“We do have a way to become more active in this. It can be changed,” Comeford said. “The more of us that become aware, the more we use our collective power to force these changes.”

Editor’s note: This story has been changed to reflect that Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble was sponsored by both LingoFest and Utah Digital Humanities.

David Ferro • Feb 7, 2019 at 6:39 pm

Two comments: [corrections in brackets]

Noble, a researcher on gender and race bias in media, discussed search engine algorithms for LingoFest 2019 [and Digital Humanities Utah #4] on Feb. 1 at the Elizabeth Dee Shaw Stewart Stadium.

LingoFest is an annual two-day conference that invites technologists, students and academics to speak on a variety of topics. [actually, it is focused on voice technology]