As public interest in cold cases continues to rise, Utah investigators fight against time in their search for answers among fading memories and decaying evidence. Families continue to hold out hope, but fear their case may never see closure.

Darcie Housley has been searching for answers since the death of her son, Brian Housley, who was killed in a drive-by shooting in Ogden in 2017. The grieving mother says she has been living with the fear that she will die before she sees her son’s case solved.

“That’s my biggest fear,” Darcie Housley said. “That I’m going to be dead and gone before they ever solve this.”

Brian was shot from an unidentified vehicle in the middle of the night on Nov. 27, 2017, as he was working on his neighbor’s car. While investigators have determined that Brian was not the intended target, the lack of witnesses and inconclusive ballistic evidence have made the case difficult to solve.

‘An ongoing nightmare’

Darcie Housley has since taken an active role in the investigation of her son’s death. She has worked with multiple investigators, but has been continuously frustrated by the lack of communication. She said that she received one phone call during the investigation, but all other communication was initiated by her.

“I didn’t think I was being obnoxious,” Housley said. “I’d maybe send an email about every six to eight weeks, and I’d wait and wait for weeks before I’d hear anything.”

Housley has since created a facebook page dedicated to seeking justice for her son and continues to educate herself on the justice system, cold cases and what can be done to help move her son’s case forward.

“It’s just turned into a cold case, that’s been an ongoing nightmare,” Housley said.

Cold cases present unique challenges to investigators; the first being when to consider a case cold, as there is currently no nationally recognized definition for what constitutes a cold case.

In Texas, any homicide or missing persons case in which all leads have been exhausted is considered a cold case, regardless of how much time has passed.

California, on the other hand, has many different cold case units across the state, each with their own definitions and guidelines.

Utah has no specific definition for cold cases; but there is a state bill requiring any unsolved homicide or missing persons case to be added to the state-wide cold case database once the case reaches three years since the incident.

While a cold case is often thought of as being an older case, such as the Black Dahlia case of 1947, many cases on the database are much more recent than that. About 58 of the cases on the database are from the last 10 years.

Though these cases may not be as old, they still present investigators with similar challenges, hence the need for a better definition of what constitutes a cold case. This is especially prominent as cold cases skyrocket in public interest, which is putting a lot of pressure on police agencies to learn the best ways to investigate these cases.

Detective Ben Pender has been working the Unified Police Department’s cold cases for nine years and is very familiar with the challenges pertaining to cold cases.

Pender said his most common challenge is “running into people that we can’t talk to because they passed away, or for some reason we can’t find them.”

He added that many cases may have evidence that was either lost to degradation over time, or possibly never collected at all.

“I don’t think in these early ’80s [and] ’70s cases, no one was really thinking about DNA,” Pender said.

Dave Cawley, investigative journalist for KSL and host of COLD, a cold case investigation podcast, says that there’s always a risk of evidence being lost to time with older cases.

“If records aren’t meticulously kept, the longer it goes, the more likely that facts, details [and] evidence will be lost,“ Cawley said.

Cawley also pointed out potential downsides of the public interest in cold cases.

“We live in a time where there are a lot of people doing what I would call open source investigation,” Cawley said. “They essentially will conduct their own investigation, whether they realize that or not.”

Cawley said this can damage the reputation and relationships between journalists, families and the public because it becomes harder to differentiate between well researched facts or theories.

“They don’t come to it with a background in journalistic ethics and they misstate facts or they latch on to sensational details,” Cawley said.

It’s also important to recognize that while cold cases garner a lot of public attention, they rarely end in a conviction. According to a 2012 survey of police departments across the country, only about 1 in 100 cold cases ends in a conviction; however, the researchers stated that number is highly unreliable, as it is based on estimates of a relatively small pool of responding agencies.

While there isn’t any current database kept pertaining to resolved cold cases in Utah, Pender said his department has solved 10 homicides and three missing persons cases, and is currently working on another 34 unsolved homicides and 14 missing persons cold cases.

The good news is that public attention is also moving cold cases forward. It has led to more resources for investigators, such as the Cold Case Review Board, which was founded in 2020 and consists of 30 members across many departments, including forensic experts and experienced investigators.

The board meets monthly to review a case brought forth by a Utah Police Agency and works together to consider all the aspects of the case before making recommendations for the agency’s investigation.

Kathy Mackay, a cold case crime analyst for the Utah Statewide Information & Analyst Center, is one of the key organizers of the board and the cold case database.

“I can honestly say that a lot of Utah cases are being actively worked,” Mackay said. “The rewarding part is when a case is closed and you get to go sit in the room with the family when they are told that their case is closed…It is the most amazing thing.”

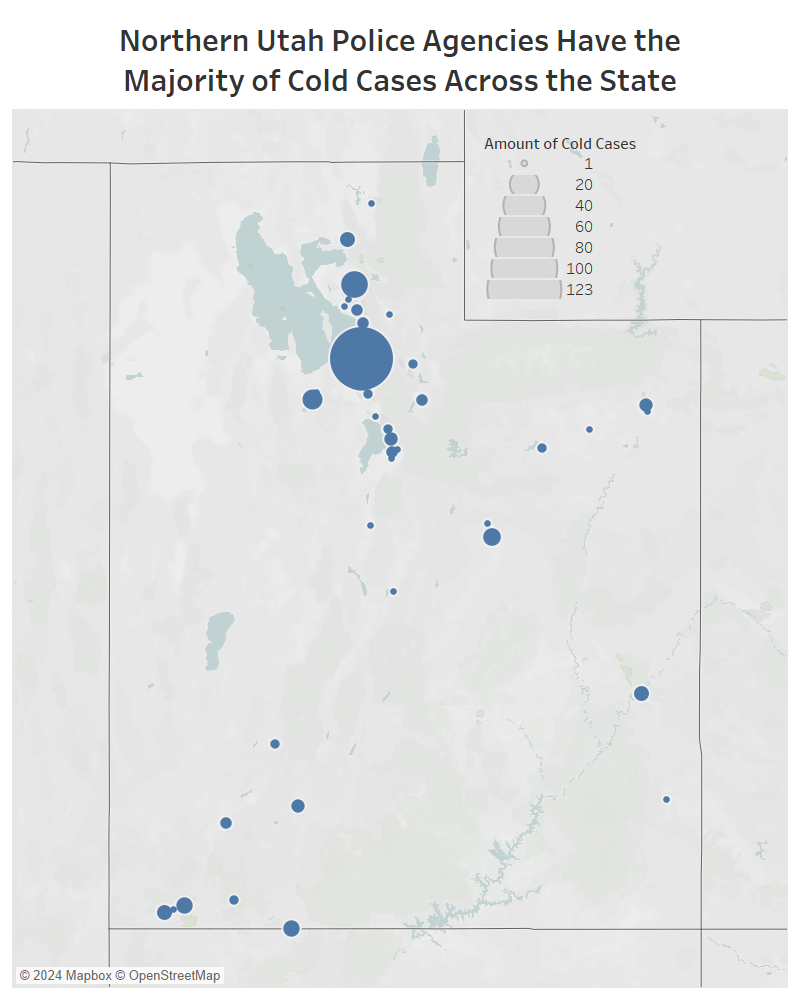

Currently, the Utah Cold Case Database contains 428 cases, of which about 58% are unresolved homicides, and another 29% are missing persons.

So far, the cold case review board has reviewed 33 cases, according to Mackay. One case was later resolved in the identification of Robert Holman Trent, whose remains were found 66 years ago in Millard County. The case was resolved when DNA from the remains were found to be a match against Trent’s daughter, who is now 90 years old.

In addition to the cold case review board, the state offers multiple grants to assist agencies with the costs associated with forensic testing through the state crime lab.

“There’s so many good stories going on right now and active cases that are being solved because of grant funding that we have available, and also because the agencies are moving forward, ” Mackay said.

The investigators working on the Brian Housley case have presented it to the cold case review board, according to Mackay. She said that it was a hard case, and so far nothing has come from any forensic or ballistics testing the agency has tried.

“We’re trying to get as many cases presented because of the families,” Mackay said. “I followed Darcie Housley on Facebook and I wanted to get her son’s case there.”

Rick Childress, the cold case investigative coordinator for the Ogden City Police Department, said that he has witnessed the expertise and resources from the cold case review board first hand.

“It’s a great resource,” said Childress. “I was really surprised at the quality and the quantity of the input that was coming from investigators, from the state lab [and] from prosecutors.”

Childress said he has presented five or six different cases, and that it has been a simple process to request a case to be reviewed. He added that creating a thorough presentation and having a good understanding of the case is key to getting the most out of the experience.

“The amount of information that comes out of those presentations is really amazing,” Childress said. “It’s great input that I think every department should be using.”

While the review board is a great resource for generating ideas to help progress a case, how the agency uses that information is up to them, Childress said.

‘The colder these cases get’

Utah offers these resources to support cold case investigations; however, the actual process behind who investigates cold cases and how much time is dedicated to them varies from agency to agency.

Housley strongly believes that Ogden needs a dedicated cold case unit. She said she’s sent letters to local politicians expressing a need for the unit to help solve cases like her son’s, which she feels has been left on the back burner.

According to Housley, the only response she received was from the Ogden City mayor’s office, which said that the Ogden Police Department has all the resources they need.

“The colder these cases get, they’re just going to get left to be unsolved,” Housley said. “They only look at it if they have time and if they get some pressure.”

Childress said the Ogden Police Department gives investigators the option to voluntarily investigate their agency’s cold cases. He said they have 22 investigators total between the major crime and special victims units.

“We hope that we’re being efficient by allowing more investigators to work them,” Childress said.

Childress added that in 2010, he worked as a full-time investigator dedicated to cold cases for about three years, but at the time there weren’t enough cases to justify a full-time investigator.

Childress said he believes Ogden now has enough cold cases to occupy a full-time investigator role, but the challenge is the current workload on investigators. He said in order to move an investigator over to cold cases, they would have to find a replacement for them in their unit, and then pull another officer from elsewhere.

The Unified Police Department of Greater Salt Lake, on the other hand, has dedicated Pender full time to investigating their agency’s cold cases, and he does so with the assistance of one part time civilian.

According to the Utah cold case database, of the 305 cases with an agency listed, the Ogden Police Department currently has 16 open cold cases, and The Unified Police Department has 48.

‘It begins with a commitment’

The public interest in cold cases helps investigators in other ways as well.

Kalra Beler, homicide cold case investigator with the Riverside Police Department in California, said they use the popularity of cold cases to their advantage.

“People are very supportive and very interested in cold cases,” Beler said. “I’m getting ready to do a press release. It should come out in the next week on an unresolved one, looking for assistance. So it will probably gain some media’s attention and some community attention.”

Beler said her department, which oversees the famous unsolved death of Cheri Jo Bates, communicates consistently with journalists to publish case details in hopes of attaining new information from the public.

Childress shared a similar sentiment, stating that his department values public input. He said in addition to setting up a cold case booth at local events, his department also uses social media to share photos in remembrance of cold case victims on the anniversary of their death or disappearance.

“We’re putting this out for the community because we haven’t forgotten and we don’t want the community to forget,” Childress said. “We want it to always stay in the forefront of their minds that there is an individual who has been murdered and that we are pursuing justice for that family and for that individual.”

Detective Pender said the most important factor that has helped his department succeed at solving cold cases has been a commitment from everyone involved to making cold cases a priority.

“I think it begins with a commitment from the cities, the police chiefs, [and] the sheriffs,” Pender said.

He added that he understands the challenges police departments face on a daily basis, especially when it comes to staffing. However, cold cases aren’t solved by simply working on them as they have time. He urged that they have to be a priority.

“Is a current [case] more important than one that happened five or 10 years ago? I don’t think so. I think they’re all important,” Pender said. “We want to try to resolve these for everybody. I think the ones that are even older deserve the same attention as the ones that have just happened.”

As for Housley, she remains hopeful for the future. She said she is working closely with the two detectives currently assigned to her son’s case, and will never give up in her search for answers.

Jill Zuger-Doetsch • Apr 17, 2024 at 12:38 pm

I worked as a composite artist for the State Police crime lab in Salem OR for 8 years. I would love to help on cold cases. Some people can still remember details years later.