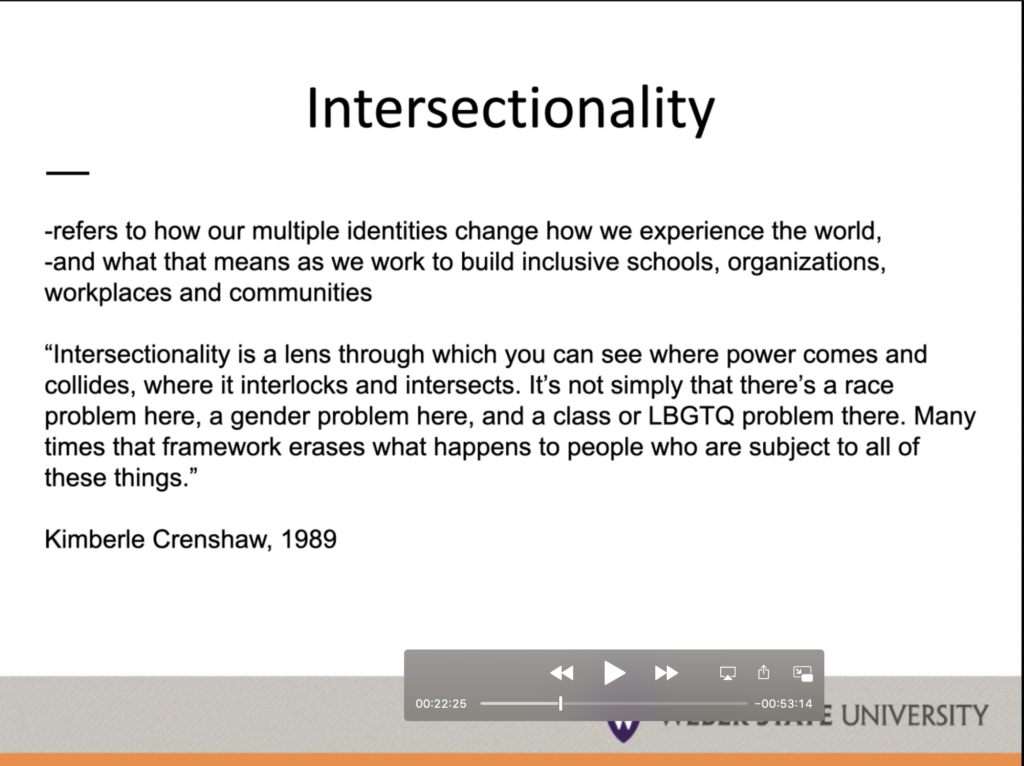

Andrea Salcedo, mentor adviser for Access & Diversity, and Olga Antonio, mentor coordinator for Access & Diversity, led the discussion on intersectional identity at the “Honors Program Food for Thought” seminar on Feb. 24. They explained the need to consider all parts of someone’s identity when considering their lived experiences.

“When different identities intersect, it’s where that power, that disadvantage or advantage, collides and connects and it intersects,” Salcedo said. “It’s not just about specifically race or gender; it’s about where those intersect and all the other identities that you hold.”

Antonio said intersectionality refers to beliefs that oppressions are linked and will not be solved by only putting ourselves in one space.

“I will not solve all of my issues by going to a space that only talks about being a woman if they don’t also talk about being a woman of color,” Antonio said.

Both women said people need to consider everyone’s identities and where they intersect. According to Antonio, these intersecting identities also shape what one should do when working towards inclusive schools, organizations and other spaces we inhabit.

“Are you inclusive of all those different identities that you may encounter in your peers in your classrooms?” Antonio asked. “When you’re teaching, are you taking into account the different backgrounds that students bring with them? They don’t leave those at the door.”

Antonio and Salcedo think it is vital for Weber State University faculty and staff to consider intersectionality in class discussions, curriculum planning and other decisions that affect students. When making these plans, faculty and staff should contemplate all aspects of someone’s identity.

“Have you ever been in a situation where you may be forced, pressured to or encouraged to pick that one thing that you most want to be in that space?” Antonio said. “Maybe asked to hide or forget or not pay attention to other things that you also care about?”

Salcedo added some people may only consider the aspects of their own identities that have been disadvantaged because it is uncomfortable to consider the identities that have a history of oppression.

Salcedo and Antonio have heard how even the jokes a professor makes can make a student hide a part of their identity throughout their time in a class or an entire program. Antonio shared an example of a married woman who was a medical student and whose professor joked about religion.

“But now that student that identifies as that particular faith feels they cannot bring up that part of themselves in the classroom, into their future goals of being a medical professional and into the discussions had with their peers,” Antonio said. “The professor isn’t taking into account that this person is a woman and professes the faith they just made fun of.”

Groups and organizations may only focus on one particular identity at the university level. This focus may enable leaders not to consider the intersection of members’ identities.

When Salcedo was a student, she said sharing a particular identity with other students in a Hispanic-focused organization was great. Still, the group didn’t consider socioeconomic or gender intersections in her experience, which can lead to the exclusion of students.

“Imagine you’re in a club, you’re so proud to go celebrate your culture, go to a conference, and you have to buy clothing or pay for something,” Antonio said. “Everybody’s so excited to be proud of being whatever this identity is, but you can’t join in on the excitement because your socioeconomic status may be preventing you from doing that.”

In this example, besides the student feeling excluded from the event because of their socioeconomic status, they may also feel they don’t relate to the experience like everyone else in the group, leaving them to feel like an outsider with that particular identity.

When discussing barriers a community may face, Salcedo said people tend to want to focus on one overall identity. She believes that this is sometimes how issues are framed at the university level, with only one particular identity being focused on at a time.

“It’s like we’ll address these students’ needs first, and then we’ll address these students’ needs later,” Salcedo said.

According to Salcedo, people at the university level need to be aware this happens and should not be afraid to push back on it.

“By including those students, we don’t disadvantage the folks that you were initially focusing on, which I think is sometimes the argument,” Salcedo said.

The peer mentor program in Access & Diversity has been reading the book “So You Want to Talk About Race” by Ijeoma Oluo. The group has discussions on the book in order to be more comfortable with these difficult conversations.

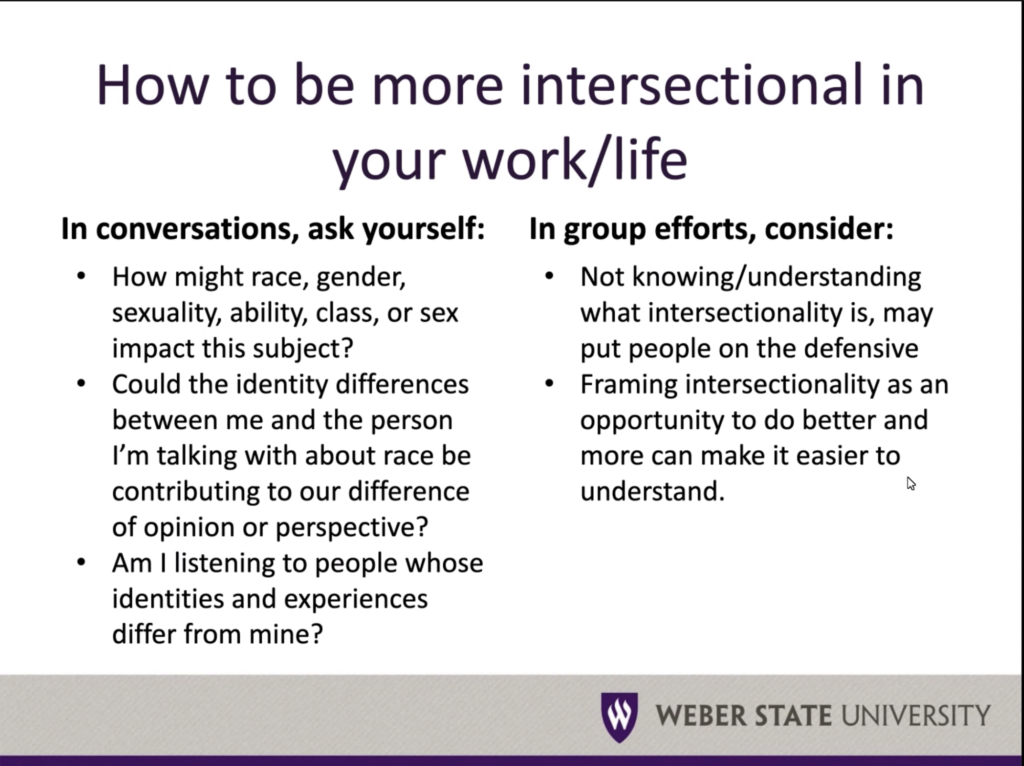

Salcedo used questions from Oluo’s book as examples that everyone can ask themselves.

“How might race, gender, sexuality, ability, class or sex impact the subject or topic?” Oluo wrote. Another question asked, “Am I listening to people whose identities and experiences differ from mine?”

While stressing the importance of these questions, Salcedo asked the audience to take the time to listen to people who identify differently or have different experiences. One should consider how a person’s identity may impact their perspective.

It is also important to frame the discussion in a positive manner.

“Framing intersectionality as an opportunity to do better can make it easier to understand versus focusing on someone failing because they’re not being right, which puts someone at a defensive,” Salcedo said. “We just need to do a little bit more, or we can do what we’re doing even better by being intersectional.”