Dr. Benjamin Eschler spoke to students interested in neuropsychology over Zoom to explain what a neuropsychologist does. The former WSU student explained possible academic paths to take to become one and what to expect when applying for master’s or doctoral programs.

“If it’s something you want to do, just prepare in your mind that it might not just be five to seven years before you’re out working and doing what you want to do,” Eschler said. “You may have to do two years of work, or you may have to do a master’s degree. Not to scare you, but just to prepare you and encourage you that it’s possible.”

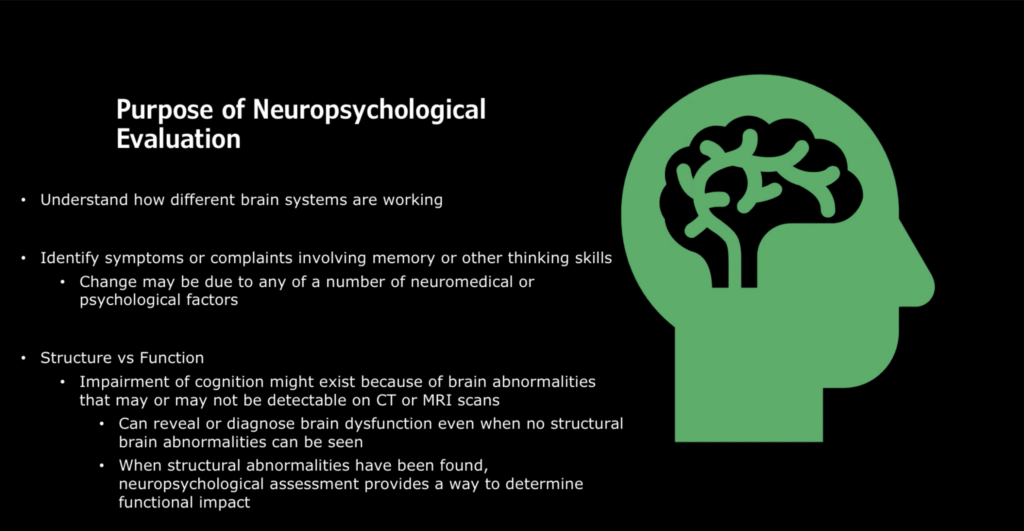

A neuropsychologist is a person with a doctorate in clinical psychology that studies the brain-behavior relationships in a person with potential memory and thinking problems through cognitive testing.

Eschler gave two different talks on March 24 for the Neuroscience Lecture Series as part of Brain Awareness Week. His second lecture was “The Neuropsychology of Brain Tumors.”

“We try and map different areas of the brain to discover different patterns,” Eschler said. “Usually, it’s to identify symptoms or complaints involving memory or other thinking skills.”

The changes in a person’s thinking and memory can occur from various disorders or diseases, such as ADHD, epilepsy, a traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s or depression. Memory changes can even happen in people with cancer, from what’s known as “chemo brain,” or from a stressful period in a person’s life.

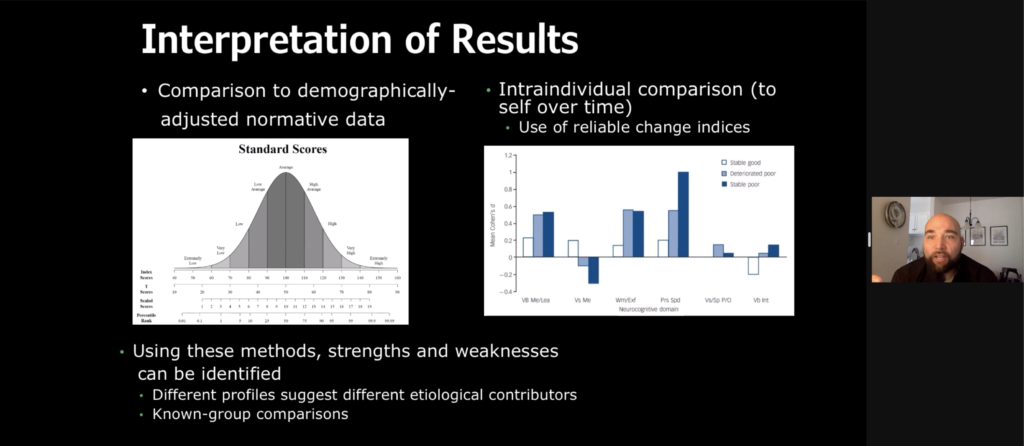

“Our tests are actually sensitive enough that I can, usually, with 80–90% accuracy, determine whether someone has Alzheimer’s or another form of dementia,” Eschler said. “We had come up with some really sound techniques to help us understand that.”

It may be hard for students to know if neuropsychology is a field of interest. Eschler compared it to the training necessary to become a therapist, since it’s challenging to shadow a neuropsychologist to learn.

“You may have learned that if you want to do therapy, but you’re not sure if you like it or not, there’s not a lot of ways to get good experience doing it,” Eschler said. “It’s similar with neuropsychology.”

As far as choosing where to take one’s education, Eschler told attendees it’s essential to know where they want to end up in their careers. An endpoint will help individuals figure out what extra education they do or do not need.

“If you want to do therapy, don’t get a Ph.D., right?” Eschler said. “If you want to be in a room with a patient doing therapy, seeing ten patients a day, then get a master’s degree; it’s done faster, you’ll have less debt and you’ll be able to do what you want to do.”

According to Eschler, it does not necessarily matter what a student’s bachelor’s degree is. However, working on an undergraduate degree is when a student should start preparing for getting into a Ph.D. or PsyD program.

“The main difference between a Ph.D. and a PsyD program is that Ph.D.s typically have more research requirements,” Eschler said. “PsyDs typically have less research and are more clinically focused.”

Eschler told attendees to begin looking through sites and information early. Students should be figuring out where they will need to apply near the end of their junior year.

Eschler told attendees that there are two ways he recommends getting the training to become a neuropsychologist. The first is to look for a job to become a psychometrist, a person trained to administer tests. The second is to become a research assistant for someone working in cognitive testing.

“Psychometrists work like a nurse works with a doctor,” Eschler said. “They are trained in administering these standardized tests and batteries.”

Research assistants can administer similar tests and receive the vital training necessary outside of a clinical setting.

Eschler said that when he was writing letters for his doctorate applications, he was not being specific about his research interests. Because the letter’s goal is to get picked by a mentor, it’s important to be particular.

“I remember saying, ‘I like autism, I like language, I like traumatic brain injury;’ the wrong tactic,” Eschler said. “You want to be very specific; they don’t want just someone that can do anything. They want to know you’re going to come in, you’re going to be committed and you’re going to be productive.”

Before a student can graduate with a doctorate, they need to do a one-year internship. An internship requires students to go through a matching process where they will pay to submit applications to each site and, if chosen, will be interviewed.

The student and the site will both rank each other, and the results get submitted to an algorithm. On the day everyone is matched, the site will then tell the student if they have been accepted or not.

If a student is not accepted, the process then starts over.

“Fortunately, you don’t have to pay more money at that point, but you still have to go through all these interviews and then do another ranking,” Eschler said.

Once a student starts their internship, they will take a full clinical load. After around four months in, the student will need to look for two-year post-doctoral fellowships specializing in neuropsychology.

The matching process then begins all over again.

After it’s all done, the individual goes to Chicago for testing and credentials check, attendance verification at an accredited program and proof of an internship and a fellowship. Then the person may need to get board-certified, a requirement at some places for a neuropsychologist, such as an academic medical center like the University of Utah.

Eschler told students how important it was to learn to communicate with and solicit the advice of the many mentors available to them at WSU. One idea he suggested was to have any on-campus mentors look over applications and letters before submitting them.

“When I was applying for the first time, I thought I knew what I was doing,” Eschler said. “I thought I was tough stuff, and I didn’t have anyone read my cover letters. So make sure you’re talking to your mentors at Weber; they’re there to help, they love you, they care about you.”