Back in 2016, the U.S. Government Accountability Office was reviewing Department of Education reports when they found that 2 million students potentially eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program simply weren’t reporting that they were receiving the benefits of the program.

In other words, these 2 million students were going hungry when they did not need to.

In their report, published last December, the GAO said the biggest factor contributing to students experiencing food insecurity is income. Low income students tended to exhibit other risk factors, such as being a first-generation student or single parent.

“College hunger is widespread among low-income students and first-generation students, as well as college students who are raising children,” Senator Patty Murray said in a conference call for student journalists.

Murray, who requested the report from the GAO, has been working with Senator Lamar Alexander to re-tool the Higher Education Act so it shows the true cost of attending college. Reworked, the Higher Education Act could show potential students the costs of attending college beyond paying tuition and fees.

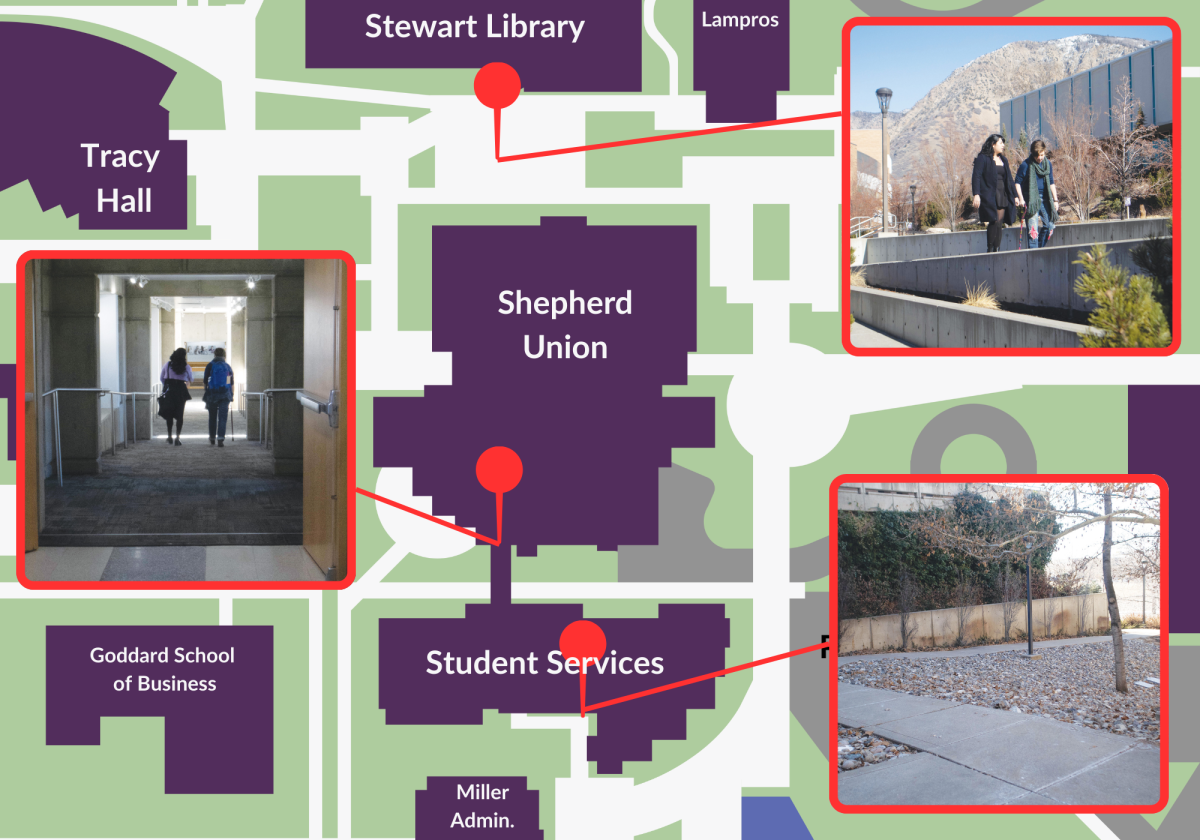

On the most basic level, this change would allow students to better prepare themselves for attending college. Currently, some universities, like Weber State University, actively encourage low-income students to attend.

The Dream Weber program targets low-income students. Full-time students with a household income of less than $40,000 annually who qualify for Pell Grants can receive full tuition and general fees through Dream Weber. Dream Weber gets these students in the door, but students still need to pay for food.

If they live on campus in Wildcat Village, they’ll have to pay for a meal plan. According to Jessica Alford, general manager of Sodexo (which provides all the food for WSU), currently 425 students pay for meal plans, the most popular of which costs $1,200 per semester. Coming up with that money, along with tuition and fees, can be a real problem for

many students.

Now, this is not a new problem. Dr. Sara Goldrick-Rab has been working on food insecurity in colleges since 2008. She said she had been having a conversation with students when an undergraduate mentioned they hadn’t eaten in two days.

Goldrick-Rab estimates that somewhere between 9 and 50 percent of students attending college struggle paying for food. At community colleges, the number of students facing food insecurity rarely falls below 40 percent.

In late January in a story by Temple Now, Goldrick-Rab noted the number of food-insecure students at community colleges appears to be sitting at approximately 56 percent. A national study by Temple University, where Goldrick-Rab works, estimated that approximately half of undergraduates experienced food insecurity while pursuing

their degree.

WSU doesn’t have exact figures on the numbers of students struggling with food insecurity, which is unsurprising. The difficulty in reporting hard statistics about hungry students lies in pinning down hard numbers. Department of Education national studies typically cost in the ballpark of $30 million, only happen every four years and, according to Goldrick-Rab, rarely include questions related to food insecurity.

Information from the Dream Weber program shows that in the 2018-19 academic year, nearly 15,000 WSU students applied for federal financial aid. Total, almost 3,000 students enrolled under the Dream Weber program. Keeping in mind that the GAO report the biggest factor for food insecurity is low income, WSU likely has at least 3,000 students who are at risk for food insecurity. Whether these students know of the resources available to them is a different question.

The GAO put out their recommendations following the report, which focused on clarity and access to information. They argued that the Food and Nutrition Service should make the rules for eligibility for SNAP benefits more clear, so students can better understand if they qualify and how to receive the benefits.

Director for MAZON Samuel Chu uses the USDA definitions of food security when discussing the problem. The USDA grades food security and insecurity on a scale where one reports on his or her food accessibility, quality and intake. High food security equates to no problems accessing food, and marginal food security equates to small anxieties about access to food or having food in the home. Low food security equates to reduced quality in food but little to no reduced food intake and very low food security equates to repeated, reduced food intake.

Chu agrees with Murray and Alexander that the next step in fighting food insecurity is updating the Higher Education Act. He believes colleges need to make a change where students are encouraged to look into food assistance instead of assuming they aren’t eligible.

National studies show colleges taking countermeasures to fight food insecurity. The GAO reported that, since Sept. 2018, more than 650 colleges said they have a food pantry on campus.

WSU’s Weber Cares Food Pantry has been open since 2011. The pantry is staffed by volunteers and stocked by donations from students and organizations. Food Pantry Chair Andrea Hernandez often collaborates with Clubs and Organizations on campus in order to bring in donations as well.

During the 2017-2018 academic year, Weber Cares Food Pantry distributed just under 5,000 pounds of food: on average, 12 pounds of food per student.

For Chu, however, food pantries are not the end-all, be-all solution. Rather, they’re just a beginning point.

“Starting a food pantry, while it’s not enough, is a good first step,” Chu said.

As far as good first steps go, the Weber Cares Food pantry works hard to ensure students have access to food when they need it. Alford noted Sodexo works closely with the food pantry, donating multiple times a week in order to ensure students can get what they need. All fundraising efforts through Sodexo go toward the pantry as well.

“We also work with CCEL to provide food vouchers for students in urgent need,”

Alford said.

As part of addressing the greater problem, Chu emphasized that administrators in contact points could be trained to help students with food insecurity. Again, the problem circles back to an issue of information access. Chu argued students should be encouraged to look into food insecurity solutions instead of assuming they aren’t eligible.

According to Provost Madonne Miner, Academic and Student Affairs talk food insecurity when they discuss ways to ease the financial burden on students. Of course, with the difficulty in identifying how widespread the problem is, direct measures to counter food insecurity are difficult to deploy.

“So we assume that it is our job to make WSU as affordable as possible by taking measures to keep costs down,” Miner said. “And, by taking these big steps, we hope we improve life affordability for all our students.”

Recent measures at WSU include changing one-year scholarships to guaranteed four-year awards, looking for ways to decrease the costs of textbooks and an increased advising presence, which all aim to ease the financial burden of attending college for students. Therein lies the crux of the matter: these people struggling to eat are students, after all, who have to pay for school and food, often for families. Ideally, then, these measures help students eat, too.