College presents a plethora of challenges that aren’t always obvious at first glance: the testing centers, a hill on the way to class or a cramped bathroom. But for students on Weber State campus with disabilities, they can be detrimental.

Of the 29,744 students enrolled in fall 2021, 858, about 2.9%, of them are registered as having a disability, the Weber State Disability Services Office says.

While many disabilities are physical, this total does reflect those with learning or mental disabilities but may not be a comprehensive number of all students on campus who struggle with a disability if they are not registered with the office.

The American with Disabilities Act defines a person with a disability as someone who has a physical or mental disability that significantly limits their day to day activities.

Cailin Hughes, who has dyslexia, said that working with the Disability Office and her professors has been a positive experience. While her professors have been accommodating, college is still challenging.

“A lot of my classes are online, and a lot of the assignments are like having to read from the textbook to get information,” Hughes said. “And that’s hard for me. I can read the chapter five times and still not pick up the information that I need to.”

Hughes said that having someone from the Disability Office read her tests to her helps with comprehension and is a good accommodation for timed tests.

“I just have to work that little bit extra to get to where everyone else is,” Ryan Charters, a WSU student who is color blind and dyslexic, said.

Charters, who is only in his second semester as a college student, said he has not registered with the disability center.

Being color blind and dyslexic, Charters has had some struggles in his general education classes, but his professors have been helpful in making accommodations without a written letter from the Disability Center.

“In math, I will often get commas and periods mixed up,” Charters said. “I remember I had to retake one of my math tests completely because I got just under 70% because of one answer.”

Charters said that reading building names on campus was hard when he first came to WSU.

Disability accommodations from high school to college can range drastically. The transition often poses a drastic change for students, especially those with physical disabilities.

Recent WSU graduate Kierstynn King said she was not given the same amount of help once entering college.

“The first time I went to the Disability Center I was with my mom, and they kind of made it sound like they would be able to help me with everything that I struggle with,” King said.

King, who has cerebral palsy that affects her ability to get around, specifically mentioned getting to class in the snow and doing math at a slower pace due to her disability.

Angela McLean, disability services director, said that higher education campuses are not under the same obligation as high schools to provide means such as transportation to classes, nursing staff and personal evaluations because college students are considered adults and are responsible for those personal needs.

“Adult education is different, and ADA is then enforced there,” McLean said. “So the personal support services and the responsibility of the institution changes.”

McLean explained that this transition can be shocking for most students and hard to handle. K-12 schools are under IDEA 504, compared to higher institutions that are under ADA.

The Disability Office works to provide peer mentors to help students through this process, provide transition counseling and help students make connections with the adult disability community in Ogden, to help with some of those issues that the university cannot provide.

But beyond that, King said that she often felt looked down on before the global pandemic and was not given access to the resources she needed.

“I don’t want to say they thought I was dumb, but they were just over-simplifying things when they didn’t need to do that,” King said.

King said she had asked for recordings of classes to review when her cerebral palsy made it difficult to get to campus. She was told that recordings or virtual class were not options by her professor.

Shortly after King asked for this accommodation, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and classes went virtual.

“I felt that there were accommodations that could be made. People just weren’t going to do it,” King said.

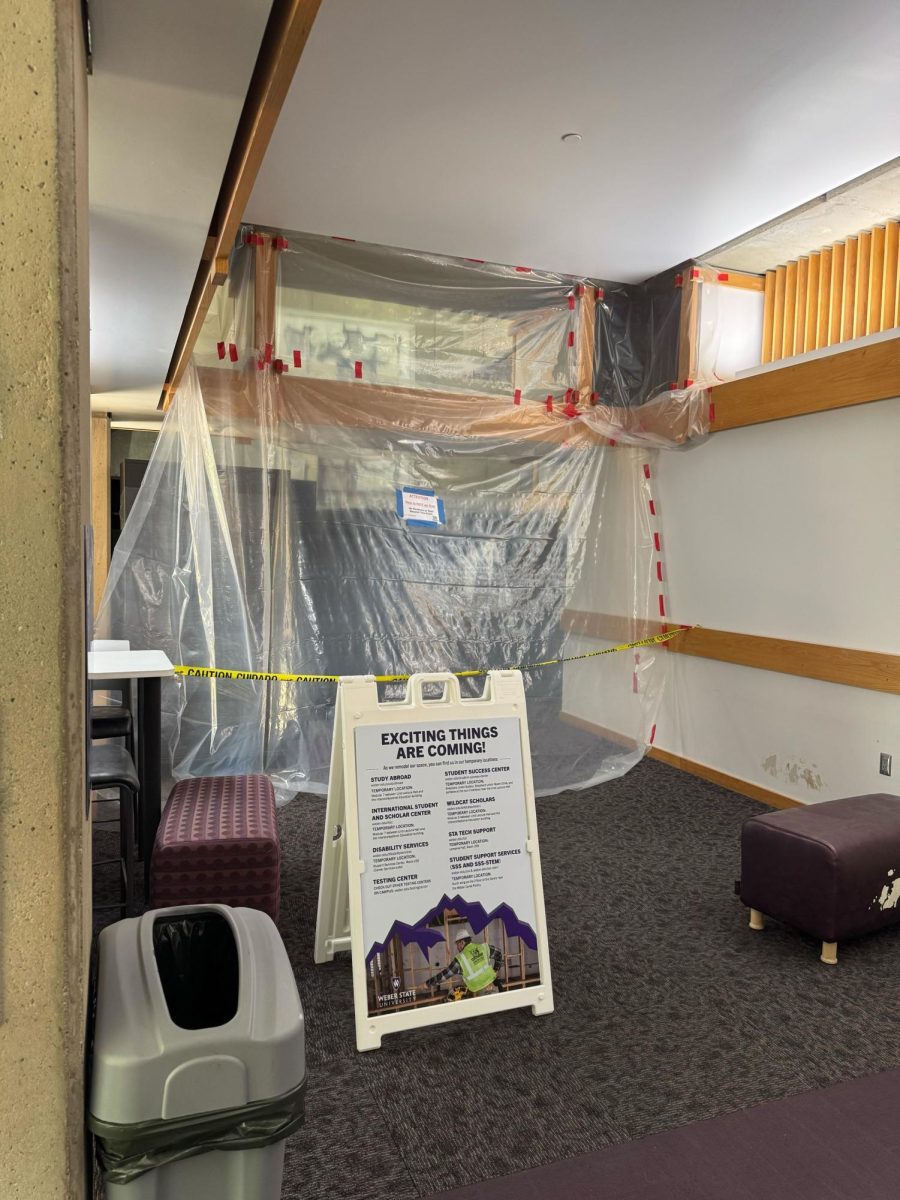

Accommodations

McLean said that most of the funding for accommodations goes to services that benefit most students in academic situations such as advising, note taking, proctoring and mentoring.

“I usually don’t have too much difficulty meeting their need because most of the accommodations that are requested are accommodations that I am familiar with,” Natalie Williams, professor in special education at WSU, said.

Williams said that students who are not registered with the Disability Center can still receive accommodations from her, but she waits for the student to make the effort to come to her and doesn’t offer an accommodation, such as extra time on tests, to everyone.

Williams said that she has made accommodations for students in K-12 and college throughout her career and works to help them find the best accommodation that will help them succeed without compromising the field or program.

Students with physical disabilities may need more than just peer help and may have more specific needs.

Annabelle Durham, whose disability is physical and mental, says that it’s the small things that can often set disabled students back.

Durham on most days seems able-bodied. She has bilateral club feet, or crooked feet, and is neurodivergent.

As a theater major, Durham signed up during the fall semester to be on the electric crew. The sign-up sheet did not specify that climbing or lifting would be involved.

“I am not necessarily scared of ladders, and I’m not necessarily scared of heights,” Durham said. “I’m scared of my own feet.”

Durham also mentioned that past roommates often saw her on her “better disability” days during Zoom school when she wasn’t walking around as much.

When she did mention her disability, they would roll their eyes at her and bully her about actually having a disability.

“It’s very common for disabled people to be pushed aside and ignored unless they are visibly disabled, and even then,” Durham said.

Durham reached out to the College of Health Professions, where the roommates were enrolled as nursing students at the time. Durham never got a satisfactory response or heard if her roommates were spoken to about this discrimination.

While the number of students registered with the disability center may seem small, Durham says there are a lot more disabled students than most people realize.

There may be more students like Charters who are not registered with the Disability Center.

Ryan Dunn, assistant professor in the Child and Family Studies department, said that some things that may not be first recognized or seen as disabilities could be English as a Second Language and the challenges of returning students.

“If you had done pencil and paper school and then came back to a computer-based school, that could be a learning disability,” Dunn said. “You would not be able to show me you were good at math because the computer would get in the way.”

Some students such as Charlotte Poe, who has fibromyalgia, which causes widespread pain and fatigue, may just need to finish their degree at a slower pace.

Poe can walk, but she often uses a wheelchair because her energy is low and getting around campus can be a bit of a to-do.

“It wears me out really, really quickly — pain is really exhausting — so I use a wheelchair to help me just stay awake for more than half the day,” Poe said.

Scheduling her classes on Monday, Wednesday and Friday helps Poe give her body the time it needs to rest.

Poe also has gastroparesis, which affects her stomach movement and her weight.

“When you’re really tired and when you’re in pain all over, all the time, that affects everything,” Poe said.

As a part-time student, Poe has plenty of work, but she thinks that students should really take more time to slow down.

“I personally think that everybody should take things slower if they need to,” Poe said. “There is this whole culture of doing it now, now, now, and shoving in every class that you need to, and it seems to just cause misery.”

Poe and Durham both expressed an appreciation for first access to classes during registration that is provided to them from the Disability Center.

McLean said that many accommodations can be made for different students and disabilities are complex.

“Disability and access and equity is everyone’s job on campus,” McLean said.

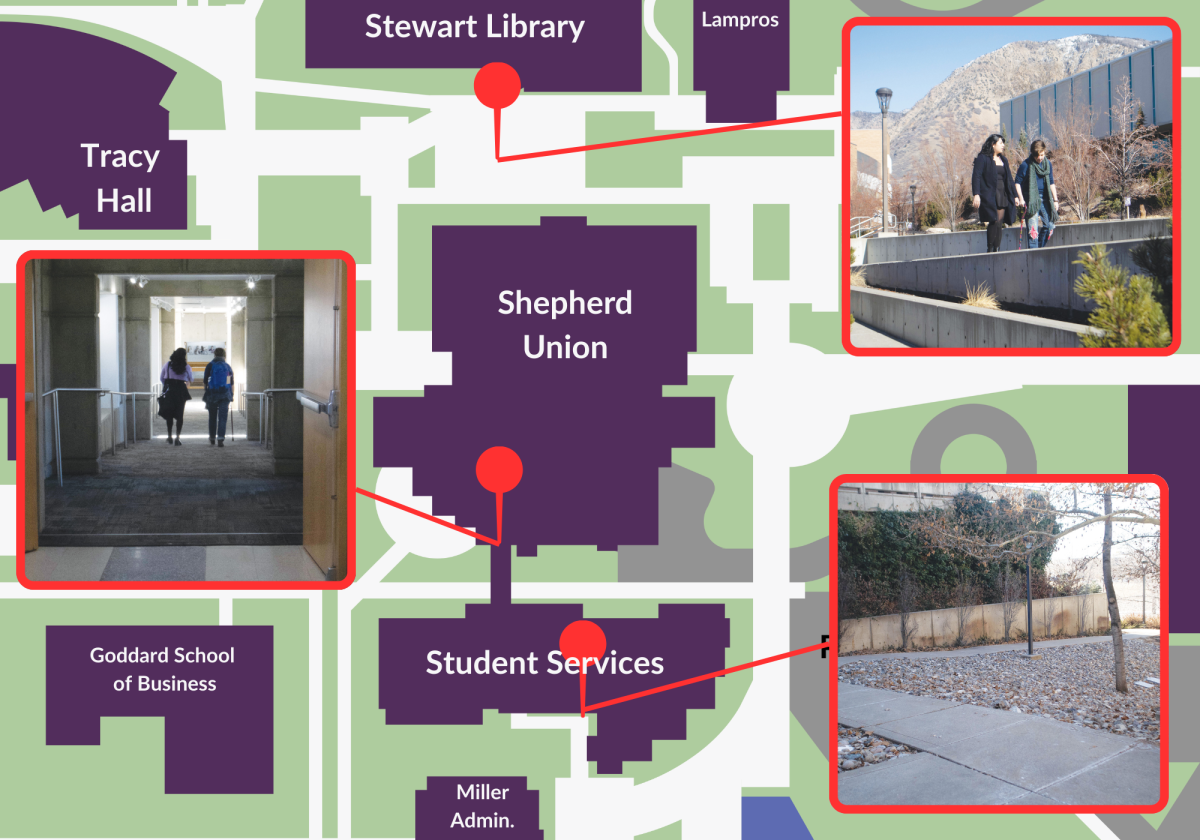

Access to advising and test accommodations may be enough for students with learning or mental disabilities, but snow removal, handicap parking spaces, elevator access and easily accessible classrooms and bathrooms are more important for students with physical disabilities.

The university’s Master Plan surveyed compliance with ADA requirements in all buildings on campus in 2016 and found many of the buildings were built before ADA was put in place in 1990.

According to the appendix of the Master Plan, the university had over 740 Priority 1 restrictions. Over half of these VCBO architecture felt that university maintenance staff could fix on their own.

Priority 1 restrictions included accessible restrooms and routes, force required to open doors, mirrors being too high, accessible elevators, wheelchair stalls in bathrooms, rooms without ramps, wireless door actuators, range of reach, chairs or obstacles blocking doors and clearance, etc.

The assessment suggested that WSU consider “systematically addressing the Priority 1 restrictions in each building in a timely manner.”

Recognizing and Respecting

Treating students on campus with respect without pitying them or coddling is what Durham, Poe and others said they want.

“It’s not like we need coddling or special treatment,” Poe said. “It’s more that we have different capacities that need to be respected and supported.”

Poe said that students who want to help should ask before acting and check in with their disabled peers every so often.

“Never assume you know what is best,” Poe said.

She added that some people will just grab or lead blind people to where they think they need to go or grab her wheelchair and not ask if she needs assistance first.

Dunn says that a desire to understand others can help to better serve them.

“That’s the thing I wish people would do, connect,” Dunn said. “I would love for there to be kind of that wonderment and curiosity and interest in one another.”

As a professor and a father to a child with a disability, Dunn says that something we all can work on is helping students feel more welcome rather than just this open-door policy.

“There is a difference between being invited and being welcome,” Dunn said.

The university does not have required training to prepare or educate professors on students with disabilities, according to Dunn, but when he has expressed the desire to attend workshops to further his knowledge, the university gives full support.

Even if students don’t have a diagnosed disability, Dunn says he encourages students to ask if something isn’t meeting their needs.

Williams said that educators should realize the students they work with are students first and should identify their strengths to help them succeed.

Rather than telling those who are disabled that they are unable to bring anything to the table, Dunn hopes that everyone can recognize that their presence is important.

Williams said that students with disabilities can often underestimate what they have to offer. These students already have the skills to complete the course or whatever it might be.

“I don’t find it difficult to meet a student where they are, I have never encountered a student in my class who has a disability who I couldn’t meet that need,” Williams said.