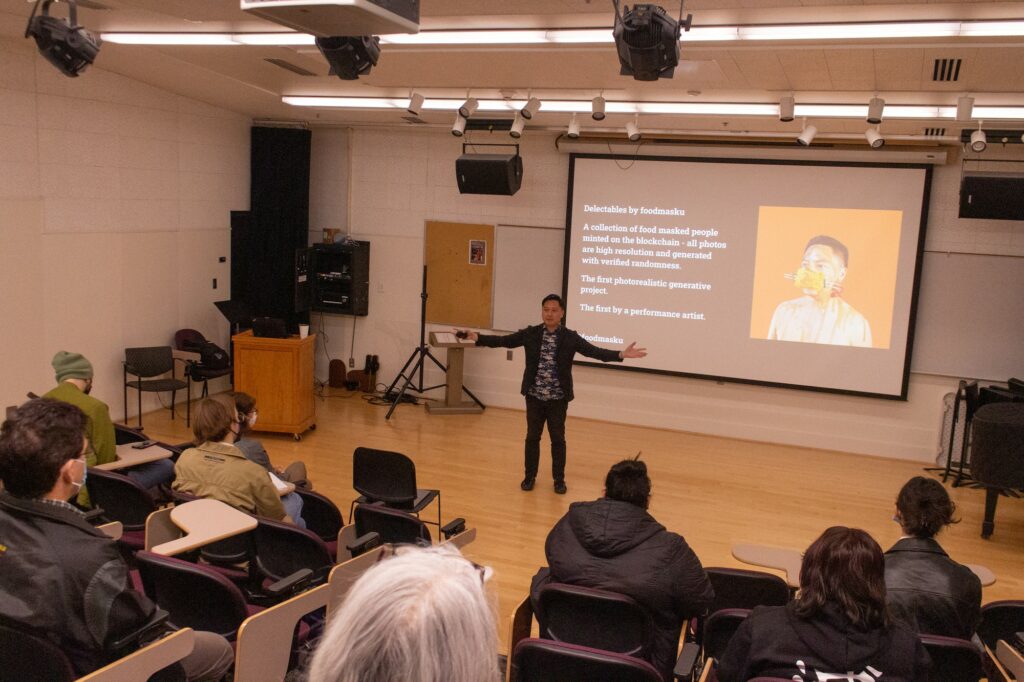

Weber State University students and faculty had the opportunity to attend a lecture given by the artist Antonius Oki Wiriadjaia on March 18 in the Browning Center. Wiriadjaia, also known by his artist name Foodmasku, focused his lecture on the intersectionality of art and technology.

The former Fulbright scholar is well-known for his Instagram account “Foodmasku,” where there are many photos of him wearing masks made out of various foods.

The project first started when Wiriadjaja was in a Zoom call, and a fellow artist was using one of Zoom’s face filters to alter their face into a pickle. In a small moment of humor, Wiriadjaja stuck a piece of kale to his face like a mask, and from then on, he began his Instagram account that documents Wiriadjaia making different facial coverings with various kinds of daily foods.

Wiriadjaja began his lecture by talking about his history and work before Foodmasku, highlighting the music video he made for the artist called Saudi. He also highlighted his project where he made one of the world’s largest animations of a swimming pool, which was then displayed in the Interactive Corporation building in New York.

He then elaborated on how the Foodmasku account was a play on the 100-day mask challenge.

“That was actually surprisingly popular. It was so popular that I ended up basically becoming a meme,” Wiriadjaja said.

His work became so popular that he found himself on The New York Times’ list of five artists to follow on Instagram. However, he also found himself in some more troubling times.

Wiriadjaja found that some of his artwork had been stolen and posted on other accounts or other social media sites. He expressed how this was an issue to artists like him who were posting solely for exposure. This problem spurred an interest in digital ownership and what is known as the “blockchain.”

From this research, Wiriadjaja found non-fungible tokens, more commonly known as NFTs, leading into his main topic about artwork and technology. By “minting” his artwork and selling it as an NFT, Wiriadjaja overcame the theft of his artwork.

“But at the very least, understand for once, artists actually have a chance to have ownership of something that they created and get something out of it that’s more than dislikes and follows,” Wiriadjaja said.

Wiriadjaja explained how other contracts, like licensing agreements, are short-term and never really last. However, his NFT artwork, even if resold, still has royalties given to him as the original creator. This money allowed him to make a living as an artist. Additionally, Wiriadjaja gives portions of his earnings from NFTs to various non-profits, such as trans-lifeline and fundraising for food banks in New York City.

Another point made by Wiriadjaja was the importance of digitizing artwork. When he traveled to Indonesia to learn shadow puppetry, he noted if the masters of the art he met there died, the art and knowledge died with them.

“It is our duty as artists to digitize the things we have now, the arts that we have now so we can see our future with those arts in them,” Wiriadjaja said.

Wiriadjaja spoke on the importance of seeing the benefits NFTs have, pointing out his friends and colleagues who were hit hard by the pandemic. Their galleries and productions were shut down, and their source of income stopped. However, they were able to survive by selling their artwork as NFTs online.

“By digitizing it and by turning it into non-fungible tokens, they actually were able to continue living as artists,” Wiriadjaja said.

However, only the big sales make headlines for NFTs. Those that make millions take up news over Wiriadjaja and his friends, who are getting by.

“I wish that more people would speak to artists who are using this as a way to basically support themselves,” Wiriadjaja said.