The drought in Utah didn’t give any favors in 2022, and it will continue to worsen if nothing is done to stop global warming and the handling of how water is distributed in the state, advocates and experts say.

In the Southwest region of the United States, a growing issue is the water levels around major bodies of water, particularly the Colorado River, which supports Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, California, Colorado, New Mexico and Utah.

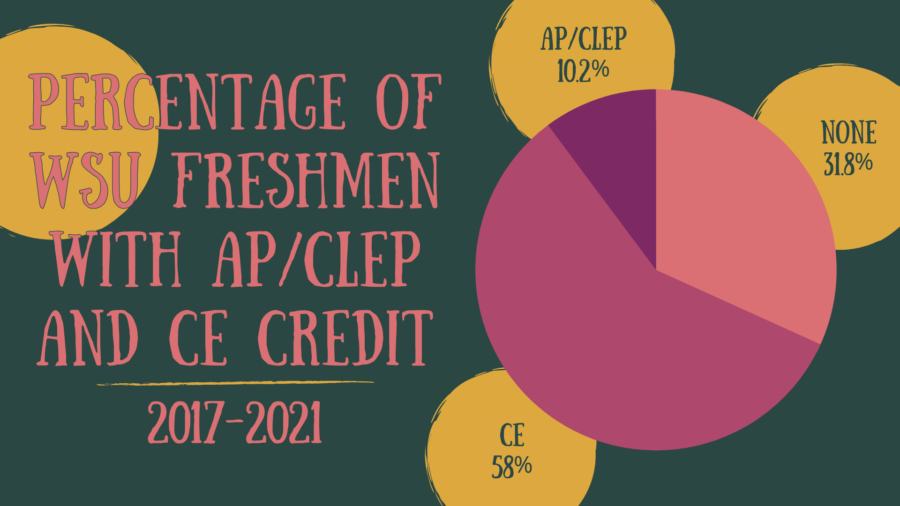

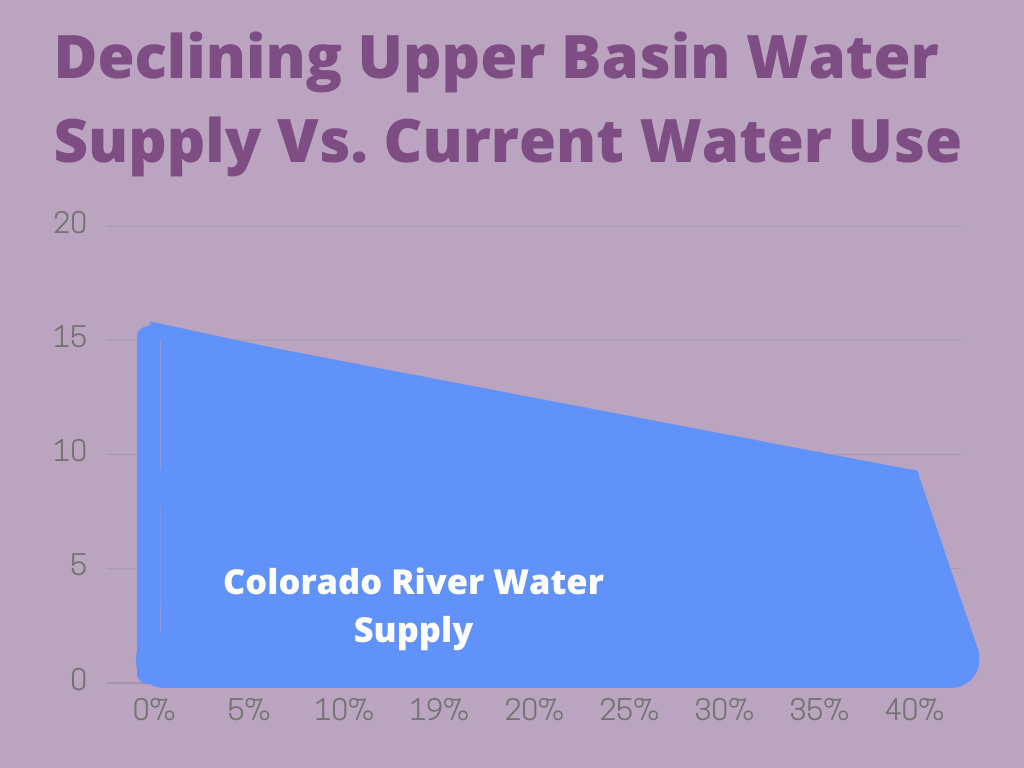

The Colorado River’s Upper Basin Water Supply has decreased from 4.5 million acre-feet per year to below 2 million, and the deficit is 35% from where it was when the 20th century began, according to the Utah Rivers Council.

Utah Rivers Council member Lindsey Hutchinson said 95% of new water added to rivers around the state comes from the snowpack accumulated each year, and with rising temperatures, the weather patterns that lead to snow don’t look as powerful or frequent as they have in the past.

“We have been in a mega-drought for over 20 years, and the longer a drought occurs, the worse they get,” Hutchinson said. “Our rivers depend on the snowpack each year, and if there isn’t a lot, then our rivers will suffer.”

In December last year and the first week of March, snow totals recorded around the state indicated that they were close to or over normal rates, but as for the beginning of this year in January and February, there was barely a trace of snow while what was remaining on the grass and mountains slowly disappeared.

The Utah Division of Water Resources has published a graph that shows the black line indicating snowfall in the state this year and how it has compared to the past.

The snow totals for 2022 peaked at about 12 inches in March, while the highest year recorded in the past 20 years was in 2011, where there was more than 25 inches.

Utah Division of Water Resources Director Candice Hasenyager said that since the precipitation levels haven’t reached normal rates, there have been negative effects on how much water Utah is losing out on.

“There are many sources of water that have been impacted by the drought here like reservoirs, dams, rivers, groundwater and spring water,” Hasenyager said. “About half of our largest reservoirs are below 40% capacity, and we really took a hit last year with rising temperatures, less snow totals and early snowmelt peaking 10 days earlier than normal.”

Snow melt occurs as temperatures increase and the snow starts to turn into water. The mountains around Utah could have snow until about May or June, depending on how hot or cold the weather is.

As a result of a very weak winter season this past year, the amount of water necessary for sustaining water levels was not attainable and increased the effects of the state’s drought situation.

Weber State University water resources professor Marek Matyjasik said Utah has been in a drought for centuries and it looks like there are no signs of it stopping anytime soon.

“Droughts are not something new to Utah,” Matyjasik said. “In the 19th century, there were pretty severe drought conditions that Native Americans dealt with and impacted their economic well being. Drought conditions existed back then and will continue to exist into the future.”

When looking at rivers such as the Colorado River, water used to be at a higher level in the past. The watermarks left behind on land masses and mountains is where there is a tan area towards the bottom as the Colorado River, at full capacity, is 27.6 million acre-feet per year.

Rising temperatures have caused less precipitation because of climate change, but the dependency on water by the general public and the amount that has evaporated due to the heat both play into the depleting water levels in Utah.

“On average, our studies showed that for every three or four people, a family uses about 400 gallons of water a day,” Matyjasik said. “For evaporation, at least 30% of our water in our water sources evaporates before the summer, and closer to 80% in the summer months.”

Another issue Utah faces is a water-wasting crisis. Broken pipes, sprinklers or other utilities as well as the illegal use of water are some reasons why Utah is losing more water than it should.

A collaborator for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, or DWR, is the Utah Division of Water Rights, which regulates the distribution and appropriation of water usage.

Utah Department of Water Resources and Irrigation Deputy State Engineer Blake Bingham said the government agency handles dam safety, well drilling and other aspects of how people get their water.

“Water in Utah is distributed based on a system of prior appropriation or First in Time, First in Right,” Bingham said. “Essentially, to divert water from a stream, well, springs or other natural sources, it requires a water right, which people file Applications to Appropriate Water in order to have rights to water.”

Even if the rest of Utah uses water efficiently, the drought will continue, as the weather has a mind of its own.

Global warming has been an issue since the 1800s, but it has accelerated from activities like the burning of fossil fuels such as oil and coal that create greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide that go into the atmosphere, trap the sun’s heat around the earth and warm the planet.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency has stated that Utah has warmed up by almost 2 degrees Fahrenheit in the last century and the chances of precipitation have diminished due to climate change.

Because of the unknown future of global warming and the drought, there are many effects that can change the way life goes in not just Utah, but the Southwest portion of the United States and possibly the rest of the planet.

ReDirect Guide Founder Mike Johnson discussed how the alarm bells should be ringing because, since 2015, the temperature has reached record highs as each year has gone by.

“As each year passes, the records are set even hotter,” Johnson said. “In July of 2021, it was the hottest month the whole world has ever seen globally for land and sea. The worst of the droughts we have ever experienced were because of the hottest month on record.”

With temperatures becoming hotter now than in the past, there are potential consequences that would happen in the future if the trend continues.

During the Intermountain Sustainability Summit at Weber State University on March 17, Our Children’s Trust Senior Staff Attorney Andrew Welle said Utah is heating up more than any other state in the U.S., and chances of adding water to the state are diminishing.

“The snowpack has decreased by nearly 80% from 1995 to 2020,” Welle said. “Utah is warming up about 70% faster than the global average. If fossil fuel development continues under business as usual, the Southwest will experience the highest increase in annual premature deaths due to heat and our water resources will continue to decrease to very dangerous levels.”

Water could drop even further, as future projections showed at the Intermountain Sustainability Summit. If Utah continues to produce greenhouse gases and burn fossil fuels, there could be a chance that the state can heat up by 3.5 to 3.9 degrees Celsius or 38.3 to 39.02 degrees Fahrenheit on average by 2100.

If the heat does live up to those projections, there is a possibility that many rivers and lakes could disappear and just be open land where water used to exist.

Even though Utahns don’t use water from the Great Salt Lake, the iconic landmark has continued to shrink and it could be vacant land in the near future.

“We have hit record-low levels this past year,” Hasenyager said. “It depends on the run-off, and we could see another record-low this year in the Great Salt Lake. The declining levels of water are very concerning as we should be all worried about the state of it right now. That’s why there is a lot of emphasis to help it.”

Multiple groups of conservationists, scientists and other experts who study the drought and global warming have the same thought process: Since temperatures will not cool down any time soon, storing and saving water is a priority.

In 2019, Utah and the DWR along with seven other states worked together to develop a Drought Contingency Plan, which would make a state monitor certain bodies of water and prepare for potential water shortages due to the drought.

Because of this, Utah, New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Wyoming, Nevada and California pursued the creation of the Drought Response Operations Agreement to bring water from upper reservoirs to push into Lake Powell if the water levels shrink to 3,525 feet since experts predict it will hit that point in the future.

It is crucial to stay above that threshold because Lake Powell helps the Glen Canyon Dam create hydropower for millions of residents in those seven states.

House Bill 242 is a secondary water metering measure that was passed with over $50 million pledged to it.

This would require the water providers to install meters on all secondary water on their systems by 2030. The money will go towards the cost of installation.

With the bill passing, the state and its water companies can keep track of how much water is being used in different areas of Utah, especially rural counties.

These meters have shown a 33.7% reduction of people overusing water in Utah, according to a State of Utah report in 2018.

The Utah Division of Water Rights makes sure that all water used around Utah is allowed using a valid water right. If a person were to have used an unauthorized amount of water, there could be action taken against the person or entity that uses more water than they are allowed.

Matyjasik suggests that storing water in an aquifer, a layer of sand or rock that is capable of storing and distributing groundwater and making gradual cuts to water usage instead of substantial cuts at once, would be more beneficial in the water conservation approach.

“If we gradually manage the water we are conserving, then it would be smarter and more effective in our society,” Matyjasik said. “If we conserve in a more gradual fashion and store water in reservoirs while injecting water into aquifers, the water is protected from evaporation.”

Some critics have argued that the Utah government hasn’t done enough to combat the crisis as some bills are passed with less restrictions and others rejected.

“There is a higher chance of drier river beds, animals that rely on water will be impacted and certain species of fish could die out as droughts get worse and not enough action is put forth by the government,” Hutchinson said.

Hutchinson said the state needs to take this seriously and there are other states that Utah’s government should take note of.

“House Bill 115 was a proposed bill that was sponsored by Rep. Melissa Garff Ballard, R-North Salt Lake. The bill would have forced the DWR to provide up-to-date summaries on water loss data and the standards of water loss benchmarks,” Hutchinson said.

The bill failed as it lost a 34 to 41 vote as the opposing majority thought that the state shouldn’t interfere with city or county water issues.

However, according to Hasenyager, the DWR is always trying to come up with new solutions to help with combating the drought as more conservation efforts are in the works around Utah.

“The drought is out of our control, and we can do a lot of things to help our water supply,” Hasenyager said. “Changing the way we use water will be the most effective in the long run.”