Abandoned mines are being closed across all of Utah, despite the pushback from local communities.

Utah is notorious for its outdoor entertainment, especially with the large mountain ranges surrounding the state. Most of the entertainment found on the mountains is usually the beauties of nature, but some of it comes from the rich history of the ancestors that founded the area.

The history of mines in Utah dates as far back as the Gold Rush in the 1800s. In the 1880s, silver and copper were discovered on Antelope Island in Layton, Utah.

Though miners were interested in finding minerals in the mountains, they didn’t have much luck in Davis and Weber County. Most mines along those mountains and in the canyons have since been abandoned.

Since 1982, there had only be 11 deaths and over 40 injuries from abandoned mines since. Despite these numbers, many of the mines in Utah are still popular places to hike.

Officials from Utah’s Division of Oil, Gas and Mining Division (UDOGM) said most of these concerns are because of hidden mine shafts people can fall into, unknown chemicals in mines and loose rocks that could cause a mine to collapse.

Patsy’s Mine was a beloved hike for Farmington residents before it was closed on Nov. 10, 2020. Residents loved visiting the mine because they were able to put a name to it, and they knew the history of the man that dug it.

“I love the history of Patsy,” Farmington City Manager Shane Pace said. “What he was doing up there was prominent.”

Patsy Morely made the mining claim in 1904, along with other claims across Davis County, and there are no records of accidents related to the mine throughout the years.

Morely originally made the claim for this mine, and other mines, on Nov. 26, 1904, with the city of Farmington after emigrating from Ireland.

Morely claimed some of the mines with Farmington City and called them Locky Boy Mine and Groof Mine, but it is unknown if either of those are the now-commonly known Patsy’s Mine.

Randy Elliott, the Davis County Commissioner, said Morely had other mines across Davis County, including on Antelope Island. However, Elliott said Patsy’s Mine in Farmington is more prominent and well known.

“It seems that Patsy was mining for gold, silver, copper, lead and other valuable minerals,” Jeff Johnson said. Johnson is the owner of TheTrekPlanner.com and spent months researching the history of Morely.

Davis County residents were upset about the closure because it was a place that had been visited for years.

“They did not take into account the citizens and the people who actually go up there,” Farmington Trails Committee member Annie MacDonald said. “I don’t feel like anybody really got hurt.”

The 1.8-mile hike is just under 1,000 feet in elevation with rocks making it difficult for those not looking for it to locate the mine.

After surviving last year’s earthquake and the mine having no visible holes in the 200-foot horizontal walk inside, visitors did not feel that it presented any dangers.

Officials from UDOGM and the Forest Service felt differently. They felt that though the mine may not have had a history of injury or death, it could easily develop issues that could cause fatalities.

The federal agencies weren’t willing to allow the mine to stay open, at least while it was located on Forest Service land.

“They’re very different from caves because they’re created in a short period of time, and they’re not stable,” UDOGM’s environmental scientist Jan Morse said. “You cannot predict what will be happening with erosion and things becoming more unstable over time.”

After discovering the plan to close it, Farmington residents reached out to UDOGM and Forest Service officials to keep it open. The residents felt that the mine had enough history and significance to Farmington that it was worth it to keep it open.

“It’s a really cool story,” MacDonald said. “There’s a lot of rich history with the mining on these mountains here in Farmington and in Davis County.”

Though the mining claims were made in 1904, there are stories from 1902 that write about Morely and his mine.

Morely dug for 20 years before retiring and moving to Salt Lake City. It is unknown the exact reason he abandoned the mine, but it is speculated that he did so because he didn’t find what he was looking for.

“There’s really not a lot of minerals in our mountains,” Johnson said. He said Morely probably found a few minerals, “but nothing worthwhile and nothing that would pay back all the money and effort he put in.”

Most of the mines in Weber and Davis County don’t hold as much history as Patsy’s mine, which is one of the reasons the residents of Farmington were frustrated with the closure.

“It’s one of the mines that got me really interested in mining history,” Johnson said.

There are documents for the other people in the area who made mining claims, but because of how documentation was done during the time, it is difficult to locate them specifically.

Johnson said the history of Morely and his mine was one of the biggest reasons as to why the mine was so popular.

Elliott fought to keep the mine open because he felt that it wasn’t a place easily accessed by those who wanted to cause trouble.

“It never really was a party mine,” Elliott said. “This isn’t the place that people go to smoke their weed.”

The mine was closed because of a federal law passed in 1977 called The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, also known as SMACRA, which prohibits coal mining on National Park land.

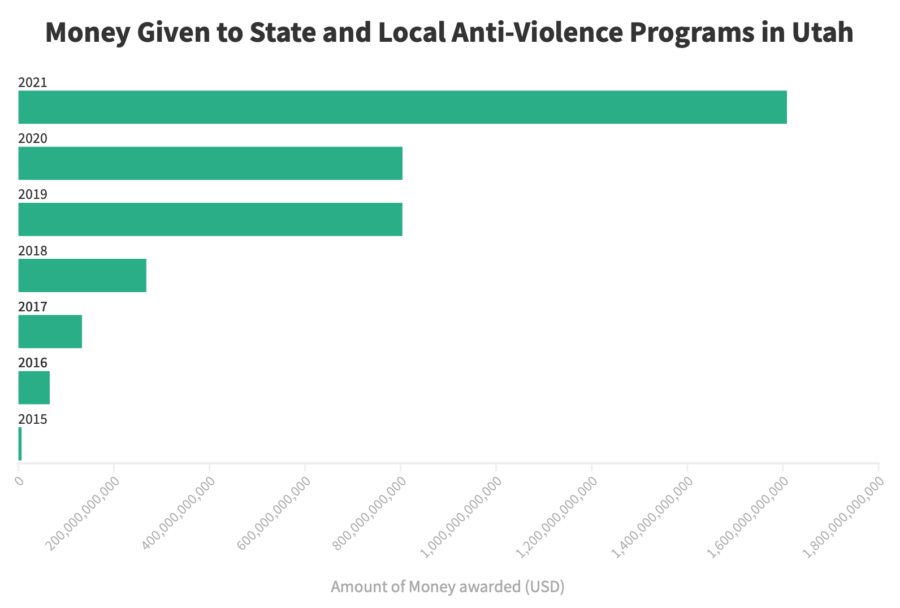

As part of the act, there is government funding given to UDOGM to close any abandoned mine across the country, even if they aren’t coal mines.

Morse said the funding to close abandoned mines comes from the taxes required for mining companies.

Bekee Hotze, the Forest Service’s Salt Lake district ranger, said SMACRA was enacted “to make sure that people didn’t just walk away from these open mine shafts.”

Morse is the project lead for the Willard Peak Project, a project to close all of the mines in Davis and Weber County, and said the mines aren’t just closed because of injuries that have happened in the past. She said these mines are being closed because of how likely it is for an injury or fatality in the future.

Morse said the biggest reason for the potential of injury is because mines have hidden shafts, even in horizontal openings like Patsy’s.

“It’s always an unknown with abandoned mines,” Morse said.

She said the federal agency considers horizontal mines just as dangerous as vertical mines because of hidden shafts someone could fall through.

Since abandoned mines are not checked daily, they could easily develop hazards. Active mines are required to have the safety of the mine checked daily, since weak points could appear due to eroding and other forces of nature.

Morse said that in a mine like Patsy’s, dynamite was used to dig into the mountain. Because of this, there are loose rocks throughout the walls and the roof. The rocks freeze and unfreeze every winter, which could loosen them more and cause them to fall.

“You cannot predict what will be happening with erosion,” Morse said. “Things become more unstable over time.”

Another hazard is that people could get lost in abandoned mines, or there could be a collapse of rocks that would trap someone within a mine.

The insurance policy to keep a mine open is usually high because of the large amount of incidents that happen inside. Since Patsy’s Mine is located on Forest Service land, the agency did not see value in paying for it to stay open.

“It goes back to that issue of liability for the landowner,” Morse said. She said the Forest Service “has been sued and they have lost, and they’ve had to pay millions of dollars.”

The process to close the mine began in 2010, when Jan Morse and her colleagues at UDOGM conducted an inventory of all the of mines in Weber and Davis County.

UDOGM is the division in charge of closing all of the abandoned mines in Utah. The agency starts the process by getting a list of mines and reaching out to the owner of the land to see if they can close them.

Most of the mines in the Willard Peak Project are located on Forest Service property, which is why the Forest Service was involved. If the mines had been located on privately-owned property, UDOGM officials would have contacted the owners of the land.

UDOGM officials reached out to the Forest Service in 2016, requesting to close the mines on the land. Forest Service officials agreed because the agency did not want to be held liable for the injuries that could happen in the mine.

In 2018, Morse said they did cultural surveys, bat surveys and other environmental surveys. This was done because of a federal law called the National Environmental Policy Act, also known as NEPA.

When a federal agency wants to take action, like UDOGM’s desire to close the mines in the area, they have to perform these surveys to make sure the area is eligible for the action that the agency would like to do.

“We will do a detailed inventory of a project area once we’ve selected it,” Morse said. She said they map the locations of the mines, take measurements, decide the best closure process and conduct a cultural survey.

As part of NEPA, Morse and her colleagues looked into all historic and archeological resources and had them evaluated by an archaeologist because of the National Historic Preservation Act. This is where it would have been decided if Patsy’s Mine would fit the eligibility for the National Historic Registry.

“If we determine things are eligible for the national register, we can create a design that preserves the elements of the site that make it eligible for the register,” Morse said.

This act requires that the action they desire to take does not have any negative impacts to the environment or people.

Hotze, the Forest Service ranger over the Salt Lake District, said they started the NEPA process in 2018. She said part of that process includes “public comments, or public outreach, to make sure that we are letting people know what’s going to happen on their public lands.”

UDOGM officials sent out press releases and reached out to Davis County officials to let them know of the plan to close the mines in the area.

Hotze said Elliott reached out to her in December 2019 about the closure of the mine. She said Elliott “expressed his concerns over this mine being closed because it’s a popular family destination.”

Between December 2019 and August 2020, UDOGM, the Forest Service, Davis County and Farmington City members met multiple times to come up with a solution that would end in the mine staying open.

“We did have a lot of community involvement,” MacDonald said.

On the Farmington Trails Facebook page, community members posted links to reach out to Davis County, UDOGM and the Forest Service about keeping it open.

“I don’t think it did anything or prevented anything, and I don’t know that there’s anything we could have done, really,” MacDonald said.

Because of the community’s desire to keep the mine open, UDOGM officials had to postpone the closure until all options had been considered.

“We went into that whole process,” Morse said. “That actually added quite a bit of time to our project timeline.”

In these meetings, the city and government officials discussed different options that could be done to keep the mine open.

“At one point, we were trying to talk about whether or not we can transfer the land to the county or the city,” Hotze said.

In order for Hotze and her colleagues to agree to transfer the land ownership over to the city or Davis County, Farmington would have had to take out an insurance policy that would cover the risk of injury and the city would have had to agree to have someone go up on a weekly basis to inspect the mine for possible hazards.

“The insurance policy was extremely expensive,” Pace said.

Though they never received a written quote, Pace said the verbal quote for the insurance policy was over $50,000 annually.

“We’re just not a large enough city to afford something like that,” Pace said.

After finding out that it wasn’t possible for the city to get an insurance policy, Pace tried to see if the mine could be put on the National Historic Registry.

“They came right back with the answer,” Pace said. He said UDOGM had already checked to see if it would qualify, and it didn’t.

Because of NEPA, Morse had an archeologist come out to see if Patsy’s Mine qualified for the registry.

There are four requirements for a location to be placed on the registry.

Officials from AECOM, the company UDOGM and Forest Service officials partnered with to close the mine, wrote in a document given to UDOGM and the Forest Service that the mine didn’t fit any of the requirements.

The first requirement states that a location must be associated with an event that contributed significantly to history. The AECOM document said, “despite retaining several of the aspects of historic integrity (location, design, setting, materials and workmanship), this site is recommended not eligible to the NRHP because the site has no associated structural remains or associated artifacts and the only features are the opening and the dump.”

The second requirement states that Patsy’s Mine needed to be associated with a person that was important to the history of the area. Though Patsy Morely was considered a local legend by some, the AECOM document said the mine didn’t have any features that were a reminder of Morely.

The third requirement states that the mine needed to resemble the era that it came from.

The AECOM document said “the site has no built features nor is it a uniquely excavated mine.” This means that it didn’t fit the third requirement for the registry.

The last requirement says that the way the mine was built needed to provide important historical information.

“This site has no further information potential past this recording, rendering it not eligible,” the AECOM document said. Because the documentation and pictures of the mine recorded everything the mine could possibly offer, this meant the mine didn’t need to be preserved.

An important thing to note is that even if Patsy’s mine had qualified for the registry, this would not have prevented the closure. It only would’ve required extensive documentation before the closure.

Morse said the officials who work to put things on the national registry “recognize that protecting human safety is more important than protecting history.”

Realizing that the closure may be inevitable, Pace said he was hoping that, by putting the mine on the registry, it would allow for signage so that people visiting the mine could still appreciate the history.

Pace and MacDonald said the city didn’t push much harder than these two options because they didn’t want the rest of the trail to be torn down.

Hikers usually stopped at Patsy’s Mine while on their way to Flag Rock, a trail that was created after Farmington City was established in 1892.

Throughout the years, hikers hung various items on top of the trail until 1997 when former Farmington City resident Randy West placed a flag on the top of a plastic pole in honor of a friend who had died.

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, West realized that the hike to the flag was the same elevation as the twin towers before they fell. Standing at 1,363 feet in elevation, a larger flag was fastened to a flagpole from an old Farmington elementary school in 2002.

In 2016, officials from the Forest Service threatened to take the flag down because they do not allow monuments on their land, but because of pushback from the community through local news channels, they did not take it down.

MacDonald and Pace were worried that if the city pushed too hard to keep the mine open, the agency would shut the trail down entirely.

“It’s really just a balance that we have with the Forest Service,” MacDonald said.

Pace said the last thing he wanted to do was to draw attention to the unauthorized flag because of the popularity of the hike.

Since the hike is on Forest Service land, MacDonald said people need to be careful and not ruin it.

“The Forest Service could come in at any point and shut us down,” MacDonald said.

The trail is not kept up by the Forest Service but by the Farmington Trails Committee, even though the trail is located on Forest Service land.

Elliott said the flag wasn’t going anywhere because of the pushback in 2016, and there was no reason for the city to back off when it came to keeping the mine open.

“There was so much public pushback that they said they’re not going to mess with it,” Elliott said.

Elliott said the issue with Flag Rock went all the way to the Washington, D.C., and it ended in them allowing the flag to stay up.

Despite Elliott’s lack of concern in pushing to keep the mine open causing the flag to be taken down, Pace said the city didn’t push much harder because of that concern.

The city wasn’t able to come up with any other solutions that would leave the mine open, but they worked with UDOGM and the Forest Service officials to see if the closure would still allow the integrity of the mine to be visible.

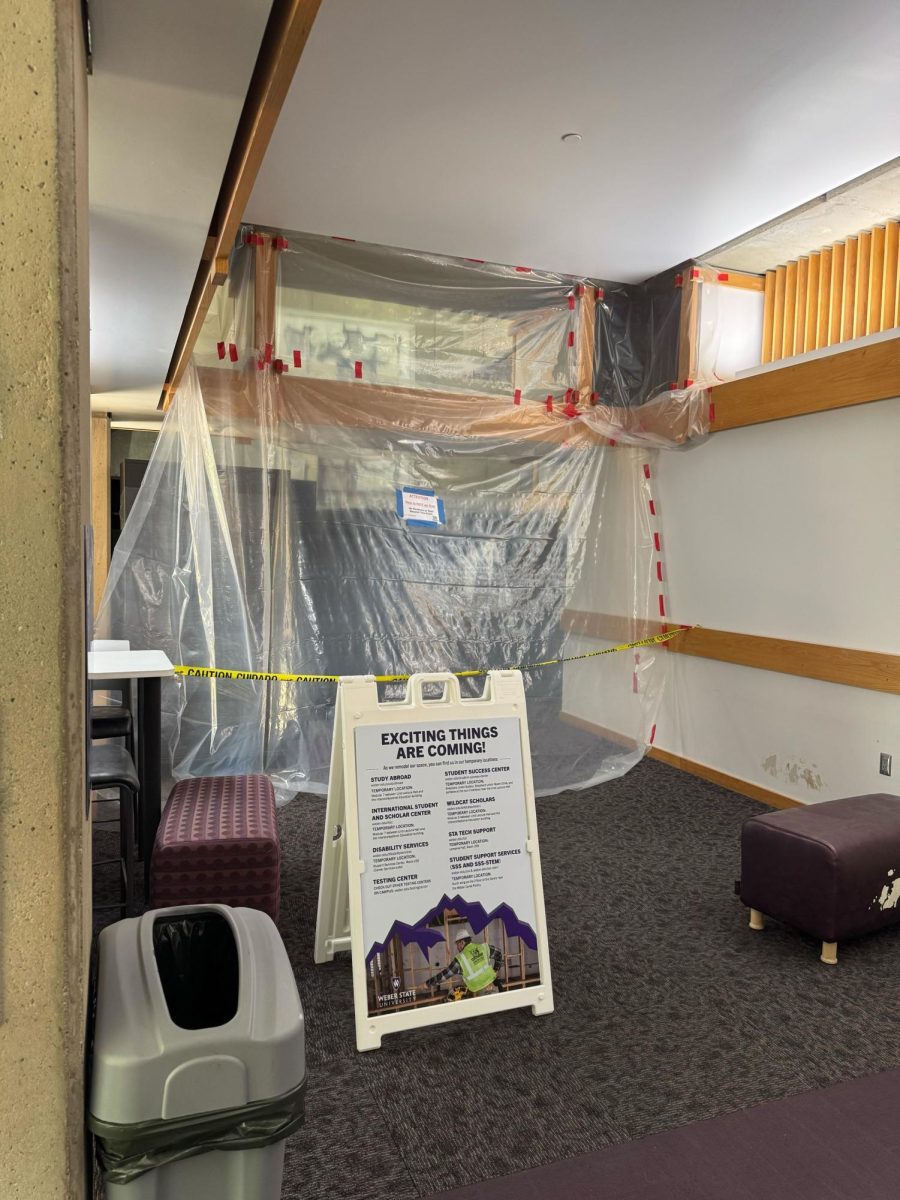

Morse and her associates ended up deciding to close it a couple of feet into the mine. This allowed the opening of the mine to stay intact.

In July 2020, Morse decided to push back the closure of Patsy’s Mine to the second phase of the project, allowing the closure to be postponed until the spring of 2021. She said she did this to allow the city more time to find solutions.

By August, UDOGM and the Forest Service agents heard the city wasn’t going to be able to get the insurance policy, and they decided to move the closure of the mine to November 2020.

In October, Morse was able to secure the funding through UDOGM to close the mine, and Patsy’s Mine was sealed on November 4, 2020 along with eight other mines in the area.

The cost to close the nine mines totaled $39,254. Patsy’s Mine cost $9,725.

These nine mines were the first of over 50 planned closures in Weber and Davis County.

“What we did in November was phase one,” Morse said.

Though UDOGM and the Forest Service officials felt that they provided sufficient warning and ample time before the closure to the city, Pace disagrees.

He said if they had had time for public campaigns, they may have been able to keep the mine open.

Pace said he received an email saying that the mine was going to be closed in 2021, and then in November, after receiving a vague email about certain mine closures, they suddenly began the closure.

Elliott said he felt there was no way to convince UDOGM and the Forest Service to keep it open. Elliott, Pace and MacDonald felt that UDOGM and the Forest Service officials weren’t very open to the idea of keeping it open.

“They all bring up the liability claims,” Elliott said. “I’m sorry, if you go on national forest property, there’s always liabilities.”

MacDonald said the closure was not necessarily because of the danger behind Patsy’s Mine but because they had the funding.

Morse said they had the funding to close the mine, and it was closed because of the possible danger that came from keeping it open.

Since the closure, visitors have tried to break through the cemented walls.

“People have already chipped away at it,” MacDonald said. She said the wall looks terrible because of it, and even though people disagreed with the closure, they should still respect it and not vandalize the mine.

“I know that this was a hard one for the public. I understand there’s been some vandalism,” Hotze said. “I just encourage people that if they have any questions about it, reach out, ask questions, find out why.”

Hotze said she doesn’t want anyone going back into the mine and getting injured.

“Just enjoy these places,” Johnson said. “Don’t do anything crazy, but just enjoy them while they’re still open.”