When Americans talk about WWII, they don’t often refer to the Japanese-American incarceration camps that spanned the country in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

These camps, created to hold Japanese-Americans suspected of being spies, began in 1942 and lasted

until 1945.

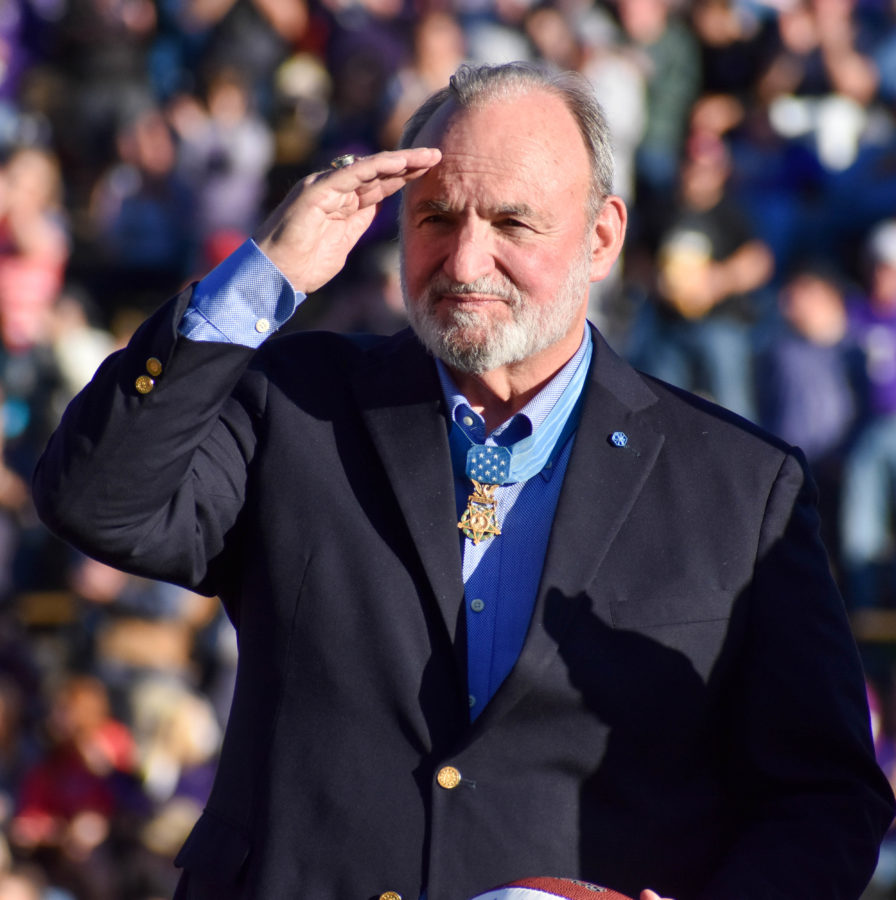

Ted Nagata, who spoke at Weber State University on Oct. 15, was held in an incarceration camp called Topaz at a location very close to Delta, Utah. There were so many people in the camp that it was considered to be the fifth-largest city

in Utah.

“It’s a complex story,” Nagata said. “But I’ll break it down into two simple sentences: most people think the Japanese were punished for something they did, and they’re not sure what they did, but they knew they were punished. They were punished for something they did not do.”

Nagata said if one were to go back 100 years to understand how white Americans felt toward “Orientals,” they would see that it’s a history fraught with conflict and dissent. Chinese-Americans provided the bulk of the work for cross-country railways and were paid half of what white men were paid, often for more dangerous jobs. However, when the railways were completed, Chinese-Americans were not invited to the celebration.

“Yellow Peril,” a term that implied the people’s of East Asia were a danger to the West, was common during WWII. Americans feared Asian immigrants coming to the U.S. would take employment opportunities from them because they’d work all day for less compensation.

In 1924, the U.S. passed an immigration act banning Japanese immigrants from coming into America. Forty years prior, there was a similar ban on Chinese immigrants.

Nagata noted that there were many hate groups directed toward Japanese immigrants before Pearl Harbor, but, after Pearl Harbor, the hate and anger reached a crescendo as wartime hysteria spread.

At this time, President Roosevelt was under intense pressure to act on the suspicions of Japanese spies. Nagata said a U.S. general went to Roosevelt with 13,000 arrested Japanese generals and suggested that they round up Japanese people and put them in camps to watch over them.

While there was no evidence of espionage, in 1942, executive order 9066 was signed, and 120,000 Japanese people were immediately put into camps, 68 percent of whom were U.S. citizens.

Nagata argued that this violated at least six constitutional violations: denial of a fair trial; denial of property rights; denial of life, liberty, and freedom; denial of voting rights; denial of religious freedom; and denial of equal protection.

In the camps, communicating in Japanese was banned. Americans worried that allowing written or spoken Japanese would lead to espionage. However, no Japanese-American was ever convicted of espionage before, during or after the war.

When the camps began, the government put up posters stating that Japanese-Americans had to evacuate and bring only what they could carry. Infamously, fine print at the bottom of the posters read the evacuations would occur on April 7. The posters were posted on April 1.

Nagata said Japanese-Americans had excelled in farming and had over 200,000 acres of farmland in California and supplied 40 percent of the produce there. The tension between Japanese and white farmers was competitive, but when the camps were put in place, it eliminated the competition completely. Most homes and farms were lost to foreclosure while the owners were held in camps.

Nagata said everyone tried to make the best out of a bad situation, but three and a half years of their lives had been taken from them. When they came back to the real world, they were broken. They took menial jobs and faced overwhelming racism and bigotry.

Nagata’s family moved to Salt Lake City, and Nagata’s mother faced deep depression and mental hardship. She was in and out of hospitals for years after the closure and never recovered. He considers her to be a true victim of the camps.

His father was unemployed after the camps, and the family was on welfare. His father did what he thought was best and put him and his sister into an orphanage. He said that was one of the better times in his young life because there was actually structure and a schedule he had to adhere to.

Nagata maintains that his story is one among hundreds, and the incarceration camps are simply a chapter in American history that goes unspoken.