For many Native Americans, the Thanksgiving story is a sanitized, watered-down version that only focuses on the light-hearted traditions and interactions between Pilgrims and the Wampanoag Indians during the first Thanksgiving.

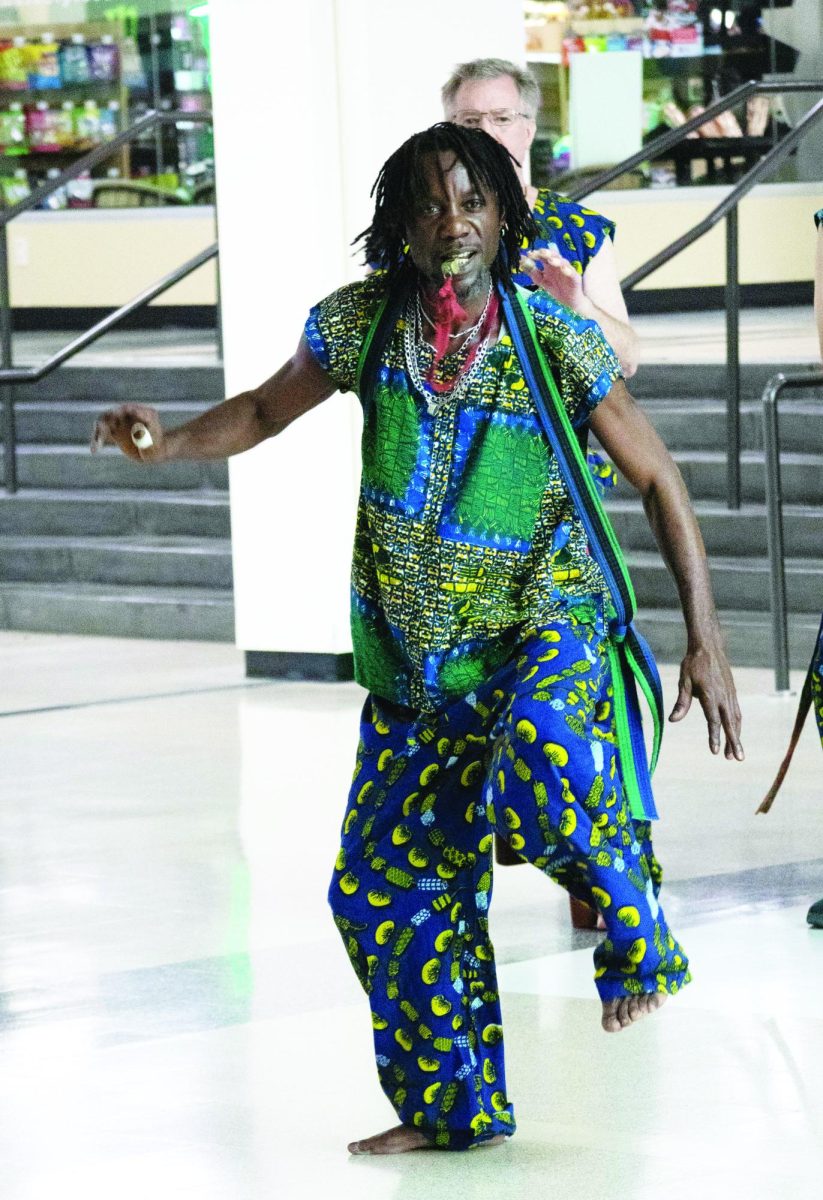

In 1621, the Wampanoag Indians and Plymouth colonists shared an autumn harvest feast, followed by singing and dancing and a prayer to celebrate the conjoining of the two colonies.

The Native Americans and Pilgrims did hold a uniting feast, but 10 years later when thousands of Englishmen arrived in the New World, their a short-lived symbiotic relationship ended. From there, conflicts between English settlers and Native Americans became a part of our nation’s history, but they’re not mentioned until children are older.

Most Americans are taught about Thanksgiving in grade school, where they often learn about the first autumn harvest feast through crafts and drawings of hand-painted turkeys and cornucopias, decorating headdresses, and roleplaying and performing skits dressed up as Pilgrims and Native Americans in their school plays.

Generally, it’s not until high school that American students learn about settlers trading smallpox-infested blankets and purposefully cheating Native Americans out of land deals and treaties, not to mention the forced march of 60,000 Native Americans on the Trail of Tears.

Since children remain largely uninformed of the injustices Native American tribes had to go through, this exposure to common misconceptions of Native Americans was and is damaging to the people and culture that helped shape the holiday.

Common stereotypes of American Indians continue to be portrayed through media outlets such as cartoons and movies, often depicting them as savage warriors and as mascots of national sporting teams, including the Washington Redskins and Atlanta Braves.

In addition, Thanksgiving Day is largely recognized by parades, televised sporting events, large family gatherings, and potlucks, and a day of rest and relaxation.

These portrayals and common practices often lead people away from the holiday’s intended historical meanings and purposes.

It was disappointing for Weber State University student Jillian Twogood when she recalled how she was taught about Thanksgiving in her school, then to learn about the long and bloody history between the two colonies years later.

“I enjoy Thanksgiving because I get to spend time with all of my family, but it’s sad that we don’t really acknowledge why we’re celebrating it,” Twogood said. “When I was younger, I was taught that Thanksgiving was the bonding between Native Americans and Europeans where everyone got along. But when I learned about its history in high school, I was disappointed, and now I think of Thanksgiving in a different way than when I used to.”

The month of November is Native American Heritage Month, and unfortunately, inaccurate historical references continue to be perpetrated annually, thus making the battle for equality among Native Americans in America an ongoing struggle.

In order to change the holiday’s infrastructure, the United American Indians of New England (UAINE) organized an annual protest on Thanksgiving Day at the top of Cole’s Hill in Virginia overlooking Plymouth Rock – where the first Thanksgiving was held.

The protest aims to commemorate a “National Day of Mourning” to honor all of the Native Americans who have died because of the United State’s government and continued suffering that Native Americans still face today.

In today’s societal climate — and depending on what region of the United States you’re in — children knowing the context and history behind holidays can make them more critical and open-minded adults.

“I think children should be taught about the facts and what happened afterward, instead of just skipping over that part of history,” Twogood said. “But it has to be taught a certain way to children, and that’s the difficult part.”

Weber State student Jenny Rubi thinks educators can incorporate serious discussions into how children are taught about Thanksgiving by relying on the facts as well as having their students engage in hands-on learning activities instead of reading about it in textbooks.

“With hands-on activities, children are much more likely to express themselves and are able to understand what educators are trying to teach them,” Rubi said. “I don’t think there’s another way to do it. Children don’t want to be lectured about that sort of thing. But I think if the serious issues aren’t taught early enough, then people tend to be close-minded about a lot of things later in life.”

So when is it too early to teach children about the historical relevancies of Thanksgiving and its dark parts throughout history?

According to Weber State student Ashleey Walters, children are already taught about dark parts of history, as early as the third grade, she remembered.

“It’s definitely a lot of information to tell children, but I remember learning about slavery in the third grade so what’s the difference?” Walters said. “It’s hard to know what age is too young to teach children about it, but there is a point where when we do teach children the truth early on, it spreads the message of tolerance and the realities of things.”

Moving forward, teaching children about the historical context of Thanksgiving should be no different than teaching them about other dark parts in American History.

By having these discussions at this year’s Thanksgiving gatherings while also enjoying the delicious foods that come with it, including cornbread, stuffing, cranberry sauce, mashed potatoes, and the infamous turkey, it may provide a stepping stone to help pave the way for equality among Native Americans, as well as all people living in America.