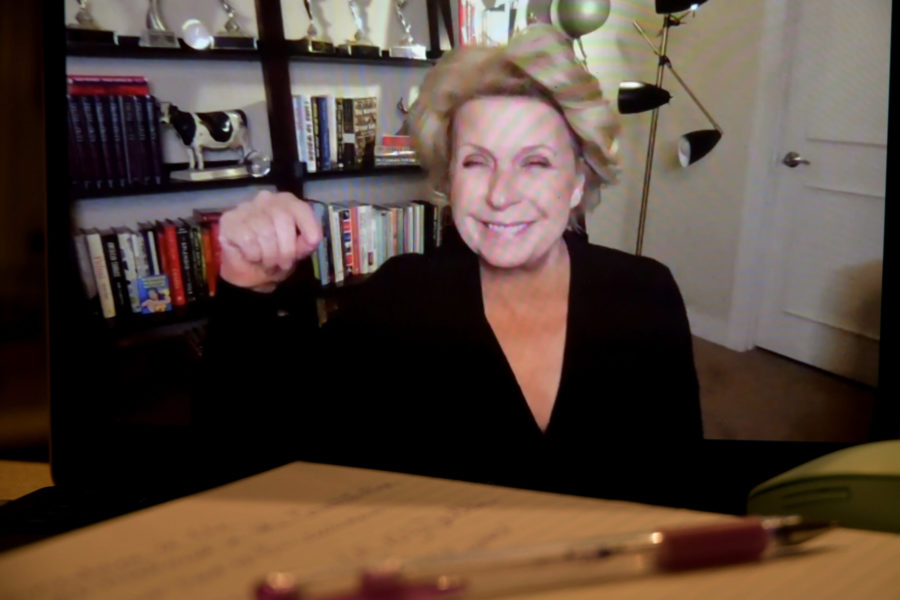

Randall Quigley, music connoisseur and music studio owner who grew up in the age of Jazz, Motown, R&B, Blues and Soul, praises music as one of the most pivotal forces in disbanding segregation and creating a culture of acceptance and respect for African Americans in post-“separate but equal” America.

Growing up in small-town Idaho in the 1950s, Quigley had never seen segregation firsthand, and overall felt no animosity toward African Americans.

“I was a junior in high school the first time I even saw a black person. He was a tremendous track runner, and I was totally blown away by the speed of that guy. I was 17 years old,” he said.

African American music, however, was an iconic part of Quigley’s life.

She said when Motown tunes first started, record companies had very specific guidelines they’d make their African-American artists follow to be more acceptable to the Caucasian population. They weren’t allowed to “bump and grind,” the men wore shirts and ties and the women wore dresses. They were taught how to eat, how to talk, when to talk and how to act.

Additionally, some of the first African-American artists who wrote music were denied full credit for their work. Producers would often buy the rights to potential hits from black songwriters and then deny the writers any royalties for their work.

Alan Hanson, an Elvis Presley blogger, wrote that Muddy Waters, an African American blues artist, thought that Elvis’ “Trouble” sounded similar to his recording of “Hootchie Coochie Man.”

Hanson also reported that Muddy Waters was thought to have said “I better watch out, I believe whitey’s pickin’ up on things that I’m doin’.”

But as time went on, the barriers began to be torn down, and the strict guidelines placed on African-American Motown singers couldn’t disguise their passion, style or authenticity.

Quigley explained that white artists began to draw inspiration from blues music and give credit where it was due.

“The Beatles would listen to records of Chuck Berry over and over again and learn the guitar rhythms he played,” Quigley said. “He was a huge inspiration to them. When the Beatles started playing black music, a lot of the lines and barriers that had existed really just went out the window.”

By the time Woodstock came around in 1969, Black artists felt freer to express themselves individually through their music.

“I mean, no one can deny that Jimmy Hendricks was totally himself on that Woodstock stage. He did the most radical things — like, you know, lighting his guitar on fire,” said Quigley.

Quigley was so inspired by the performances at Woodstock that he began fervently collecting and recording music, and now owns and operates a recording studio of his own.

“Music was the key,” said Quigley. “It really reached out and brought folks together. It was pretty hard to say you disliked blacks when you were buying and loving Diana Ross and the Supremes. That’s the power of good art. It changes people.”

Guitarist, DJ and previous Weber State student Ryan Braithwaite agrees that music has exceptional power, even now.

“Music in general is one of the first things that I talk to someone about when I meet them — it’s the first place I look for common ground,” said Braithwaite. “Everybody has some type of opinion about music, or connection to it. Music, it’s the universal language.”