In the midst of one of the strongest El Nino weather patterns in years, it’s hard not to notice the moisture falling from the sky. Utah’s supply of clean water seems plentiful now but it’s in danger of disappearing.

Recent precipitation totals are through the roof and it’s hard to remember years where hardly any precipitation fell. However, it doesn’t take a multi-year ecological survey to know that Utah is one of the driest states in the western United States. With barely any precipitation falling on Utah’s arid desert, that makes Utah’s ranking as one of the highest water users per capita in the country even more damning, according to the US Geological Services .

While that may be surprising, given what is measured in the survey, it makes sense. Utahns, per capita, use more water on lawns and gardens than do most other states because little precipitation falls from Utah skies, according to Molly Maupin, a hydrologist with the USGS, in an interview with Utah Public Radio in 2014.

According to Maupin, Utahns use about 167 gallons of water per person per day, whereas the national average is around 89 gallons per person per day, according to the 2010 water usage survey.

“Arid western states have very little precipitation in the summer, and in order to keep our gardens and our grasses green, that requires a considerable amount of water,” Maupin said.

As a leader in the Ogden community, Weber State is striving to be more environmentally friendly. Some of the most noticeable steps have been adding more recycling bins and solar panels around campus, but what is Weber State doing to conserve water? What can students do to conserve and protect Utah’s water resources?

Kevin Hansen, associate vice president for Facilities and Campus Planning at Weber State University, explained that there are two major ways the university is trying to conserve water—smarter landscaping and irrigation systems and more efficient bathroom fixtures.

Each spring students notice leaking sprinklers and excessive watering. The university is striving to fix that with a smarter, more automated watering system. Sensors attached to a new sprinkling system indicate when an area needs water or not, watering only when the lawn truly needs it, not when a timer goes off. According to Hansen, the sprinkling system is also hooked to a weather station at the top of campus near the Science Lab building. If the wind is blowing hard or it’s raining, the irrigation system will automatically turn off in an effort to use water more efficiently.

“Students get upset every year because they see us watering during the day—we have to,” Hansen said. “We have such a large campus and the capacity of our irrigation system main lines will not allow us to water the entire campus just at night. There are some areas that we have to water during the day because there are only so many hours during the night.”

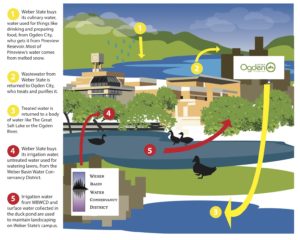

Because Weber State has to water during the day when much of the sprinkled water is lost to evaporation, the university tries to use water on campus as efficiently as possible. One way this is done is by using rainwater and other run-off that collects in the duck pond for watering Weber’s many lawns.

Hansen said Facilities Management pumps water out of the duck pond and uses it to water surrounding lawns and gardens through about July, depending on algae growth. Because the duck pond is very shallow, the water warms quickly, and algae flourish. While that is manageable to a point, the algae can clog the pump system, according to Hansen. By about July, the algae bloom gets too intense for the irrigation system to handle and the university relies solely on irrigation water from the Weber Basin Water Conservancy.

Reusing water already on campus helps cut down on the water bill, but it also helps the university take in less water in the first place.

“We are very conscious of water because we are in a desert,” Hansen said. “We try to manage our water so we don’t use excess anywhere.”

Another way the university is trying to conserve water is by installing more efficient bathroom fixtures. Students who’ve spent any amount of time in the library know about the dual-flush toilets. Similarly, many students are also familiar with the automatic faucets in the Shepherd Union and the water-restricting faucets in Elizabeth Hall.

Hansen said that, whenever possible, campus buildings in need of significant repairs will receive new bathroom fixtures, including dual-flush toilets and water-restricting faucets. Hansen said the university tried using automated faucets but found them to be high maintenance with minimal water savings.

“Right now, we have enough resources if we use them wisely,” Hansen said. “Water is a very precious commodity in the west … we have to be able to use our water resources very wisely and that’s what we’re trying to do.”

Carla Trentelman, associate professor of sociology, said students, especially those who wish to stay in Utah, cannot afford to ignore the environment.

Trentelman along with Dan Bedford, professor of geography, has been conducting research about water at Weber State through the iUtah program. Together, they found that many students know Utah is in a drought and they should conserve water, yet very few actually do. They don’t understand what Weber State is doing to conserve water or what they can do to conserve.

According to Trentelman, one of the easiest ways for students to use water more wisely is to avoid bottled water. Quality standards for bottled water are often lower than tap water, Trentelman said, and many studies have shown that chemicals in the plastic can leech out into the water, causing health problems.

For Trentelman, one of the most damning problems with conserving water is how undervalued it is by our society. She explained that as Americans, we pay only a fraction of the actual cost of the water we use. Because water costs so little and is very convenient to access, many people don’t think too much about using a lot.

“The irony is that we are willing to pay phenomenal amounts of money for bottled water, but we aren’t willing to pay for the water we need to stay alive,” Trentelman said. “Because of that, when you conserve water in a system where you aren’t paying for the amount of water you’re using there aren’t any real financial gains. If you have to spend money to conserve water, it doesn’t pay you back, or if it does it’s a very slow process.”

Another thing students can do to help preserve Utah’s dwindling water is to be mindful of what they’re putting into the ecosystem.

Alice Mulder is an associate professor of geography and the director of SPARC, Sustainability Practices and Research Center, at Weber State University. For her, taking care of the earth and protecting natural resources is a no brainer—we ultimately all live off the earth, so taking care of the earth is closely related to taking care of ourselves.

“We are fundamentally connected to the natural world. Most of us don’t think about it in our daily lives, because most of us are not particularly connected to it in a conscious sense,” Mulder said. “But ultimately we all have to eat, breathe air, drink water and we all have stuff … that fills our homes and all that stuff comes from natural resources.”

Mulder explained that there is no such thing as “away” when it comes to waste materials. Everything that gets rinsed down the sink or thrown in the trash goes back into the environment in one way or another. Just as trash is taken to a landfill, wastewater is treated and then returned to a body of water.

Mulder explained that when cleaning chemicals are washed down the drain, those chemicals don’t just disappear; they go to the sewer treatment plant. The sewer treatment plant cleans the water as best they can, but not all of those chemicals can be cleaned out. Treated water, also know as effluent, is then returned to the environment and for many in Northern Utah, that means our wastewater is returned to the Great Salt Lake. Though no drinking water is taken from the Great Salt Lake—it’s much too salty for that—we all benefit from the lake.

According to The Great Salt Lake Council, the unique biome of the lake provides Utah with not only a great recreation area, but also a financial asset in harvesting brine shrimp, salts and minerals.

In an economic report prepared by Bioeconomics, Inc. for the GSLC, it was calculated that the Great Salt Lake provides $1.323 trillion in economic output. That means between hunters shooting birds in surrounding wetlands, revenue from mineral and brine shrimp harvesting and fees collected in connection to recreational use, $1.323 trillion comes into Utah’s economy because of the lake.

According to Mulder, certain pharmaceuticals like hormones used in birth control and infertility treatments can’t be cleaned out of wastewater and can cause havoc with the effluent’s ecosystem. According to scientific research, estrogens excreted by women taking birth control ‘demasculinizes’ males, causing male fish and frogs to produce eggs rather than sperm in their testes.

While many women, myself included, consider birth control a “need” rather than a “want,” Mulder said reducing the amount of chemicals we put back into the ecosystem is a “must” for Utahans.

Currently, Utah has enough water for their needs. According to Hansen, if Utahns don’t soon curb their water use habits, there won’t be enough to go around. There have been talks of damning the Bear River, the Great Salt Lake’s largest tributaries, says Trentelman. Diverting more water away from the lake could have disastrous ecological problems, such as further salinating the lake and exposing more lakebed. More salt in lake water would make it even more inhospitable to aquatic life, and more exposed lakebed means more particulate matter in the air, especially when a storm kicks up, Trentelman said.

“We are but a piece of a bigger system,” Mulder said. “What we do and how we treat water effects the entire system and ultimately comes back to us.”