She was diagnosed with polio at the age of six and had her leg amputated after contracting gangrene, which left her confined to a wheelchair. Frida Kahlo went on to become an artist known for her artistic expression and vibrant self-portraits. Her painting entitled “Nudes in the Forest (The Land Itself)” was recently auctioned at Christie’s for $8 million.

Yet despite the success of Kahlo and other artists with disabilities, they continue to face opposition regarding their ability to excel in the arts.

According to the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), one in five people in the United States is considered disabled.

While 20 percent of the American population is considered to have a disability, their acceptance, especially in the arts, is often limited.

BYU student Kaitlyn Jacobson has been dancing since she “exited the womb.” She has a passion for dance and sees herself on Broadway one day.

Jacobson had the opportunity to attend a dance preview where the entire cast was wheelchair dependent. She said it was impressive to see how they were able to move their chairs to the beat of the music.

“The passion that filled the stage was life-changing,” Jacobson said. “I was overcome with emotion because I knew those artists had to fight for their spot on the stage.”

Dancing is aesthetic. Audiences expect beauty and grace. People with disabilities, who defy society’s definition of an ideal dancer, remain unable to integrate into a world that emphasizes a specific physique and countenance.

“I actually heard someone during the show whisper to their date, ‘She is too pretty to be in a wheelchair,’ to which he replied, ‘I know! And she actually has rhythm,'” Jacobson said.

It broke her heart to hear people judging the dancers, and she realized people don’t speak that way about able-bodied dancers. Jacobson doubted anyone in that audience was discussing the fame that awaits any of the wheelchair dependent dancers.

Another impediment people with disabilities face is simply being a member of the audience.

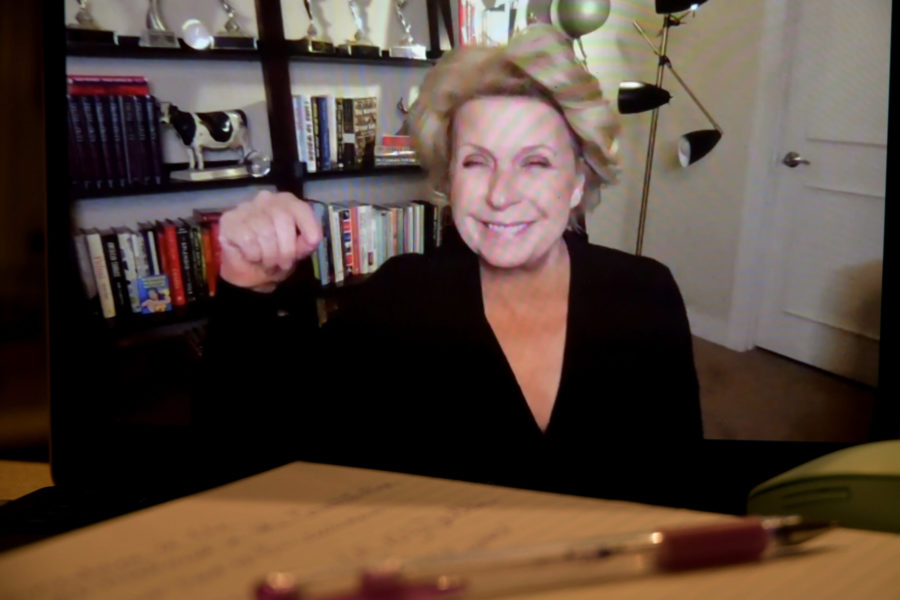

Jenny Kokai, professor of theater at Weber State University, has an inside look at the challenges regarding limited participation from those who are non-neurotypical. Her son, Oliver Kokai-Means, struggles with some learning disabilities and has a generalized anxiety disorder.

She distinctly recalls attending “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time” on Broadway with her son. It is a story about a young boy who investigates the mystery surrounding the death of his neighbor’s dog. This boy happens to have an autism spectrum condition.

What should have been an incredible experience turned out to be nothing more than pain and misery. “Oliver hated how loud it was,” Kokai said. This is an obstacle that the typical population takes for granted.

“It is my hope that more and more people will be engaged to invite non-neurotypical bodies into the art world,” Kokai said. “We will begin to see more vibrant art than we ever imagined before.”

Kokai’s close friend, who has a doctorate in theater and a passion for the arts, is also diagnosed with Tourette’s syndrome. He struggles to attend events because of the judgement he receives as a result of the involuntary noises he makes during a performance.

The lack of understanding and general ignorance about disabilities cements the stigma that people who have learning disorders or physical impairments are unable to participate in any meaningful way in the arts.

Stigmas bring forth prejudice and perpetuate this idea that people who face medically complex challenges are inferior.

Tami Youngman is a secondary special education teacher with Ogden School District and said she is “very passionate about students with significant disabilities, inclusive environments and promoting friendships and relationships across those with disabilities and those without.”

She believes education is more than academics, intended for both atypical and typical students, particularly in an inclusive environment that proves valuable to both the student and teacher alike. It facilitates friendships, advocacy and lifelong support.

“The peer mentors of today will be the same adults of tomorrow who will provide jobs for those persons with disabilities,” Youngman said.

Youngman insisted that everyone has value and, regardless of ability level, we are more similar than we are different.

There is a multitude of people who have broken the barriers that might otherwise have confined them. They challenged the stigma that comes with disability and success.

Lisa Fittipaldi wrote a book about losing her eyesight. In it, she describes her ability to tell which color she is using in her paintings just by the texture of the paint. Her pieces sell for thousands of dollars in the nation’s most elite galleries.

Dennis Francesconi has participated in more than 75 global exhibits. He suffers from paralysis but taught himself how to paint with his mouth. The intricate level of detail that he emits in those paintings, according to art critics, is what put Francesconi on the map.

Sanchita Islam developed postpartum psychosis after delivering her child and soon realized she had Schizophrenia. With very little mental health support, she discovered that drawing provided an escape from the voices in her head. She is also a painter, writer, filmmaker and author.

There’s also Vincent van Gogh, whose masterpieces sell for record-breaking prices. He, too, had what is considered a disability in that he suffered from severe depression. He cut off a portion of his own ear and then admitted himself to a mental institution.

In addition to examples of people who have succeeded, there are several programs both locally and globally that are determined to combat the stereotypes that people of different abilities face.

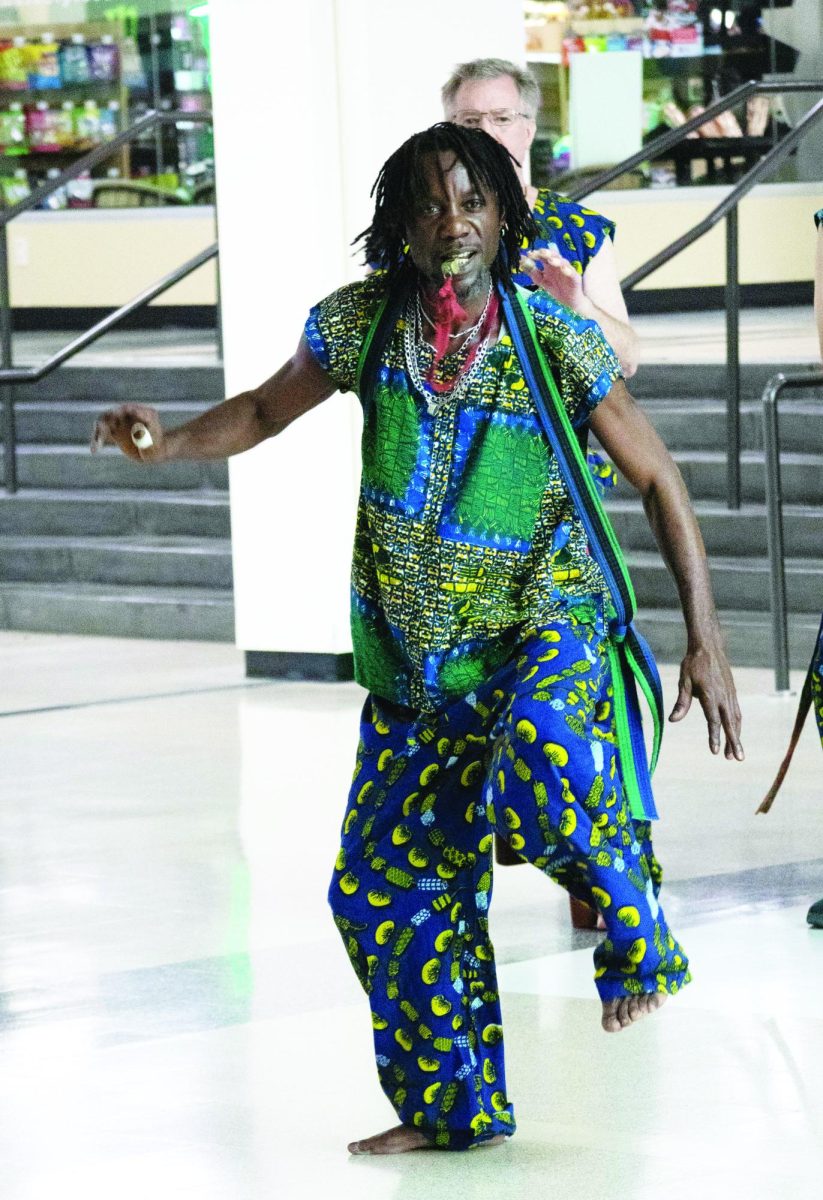

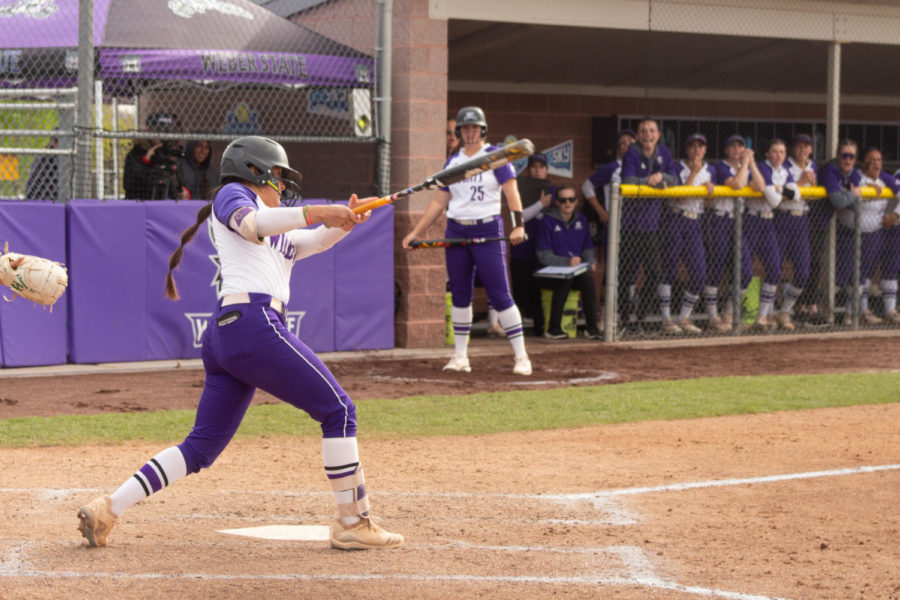

WSU is making strides to change the stereotype by offering variety enrollment for playwriting, dance, visual arts and music.

CAPES! (Children’s Adaptive Physical Education Society) is intended for children who have disabilities and their families. Led by students at WSU, CAPES! focuses on developing optimal independence through land and aquatic skills that increase knowledge and understanding in a fun environment.

Art Access in Salt Lake City fosters a program that is all-encompassing to those with disabilities as well as other marginalized communities.

They aspire to eliminate social barriers by supporting and encouraging individuals to express their identity through artwork which is then highlighted in its gallery. This month, feature artists who have varying levels of epilepsy hope to inspire the public with their intricate artwork.